One of the mysteries to people who study politics is how American Indians vote. American Indians enjoy a unique relationship with the United States, as nations both sovereign yet also subservient to the U.S. national authority. For decades, American Indian citizenship status was in limbo, and it was not until after World War I that voting rights for American Indians were firmly established.

As a consequence, little is seen in the way of American Indian voting in U.S. elections, and researchers of voting know even less than what they observe. I recently was involved in a trial in Wyoming, related to Indian voting rights, and found just one study ever written about Indian voting behavior. That study looked at Indian participation in American presidential and congressional elections, and it found, to little surprise, that Indian participation is low and structured by the education of the voter. This leads readers to conclude that American Indians' socio-economic status, or SES " poverty and education and literacy " influences voting, and that comparatively low Indian SES impedes participation.

But there is a whole other world of American Indian voting out there. As sovereigns in their own limited sphere, these submerged nations elect governors and chiefs and legislatures and business councils. Little is known about the conduct of those elections, except that voting in those contests is high. For example, up in Wyoming on the Wind River Indian Reservation, both the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapahoe tribal elections last year featured turnout rates among tribal adults comparable to the participation of voters in the surrounding county in county elections. Despite being very poor and less prone to own a home (but highly educated), Indian voters voted to govern themselves.

Why can't we know more about who participated? Well, many of the Indian nations are justifiably guarded in controlling information about their citizenship rolls and participation in those elections. The historic relationship of betrayal and distrust that grows from betrayal has soured the ability of researchers to access the myriad tribes and nations in order to conduct systematic studies of participation. What is lost in the process is a tremendous opportunity to create a systematic, comparative study of how American Indians relate to governance in their nations and also in the states and our country.

Why does this matter? It matters because the challenges of the larger world and the challenges to Indian country are increasingly the same, whether it is education, poverty, environmental concerns or economic development. In Oklahoma, the gaming industry alone shows how closely state and local government and the tribes work, coordinate and also compete, and those activities influence all aspects of public life. American Indians interact with state and local government decision makers at an elite level " lobbying, campaign contributions " but the Indian vote also can matter outside tribal politics, and litigation is becoming increasingly frequent to open up systems to Indian voter influence. Until we develop a systematic understanding of how the American Indian vote functions, and whether or not unique cultural influences might be at work on civic participation in Indian country, we will be frustrated in figuring out the best remedies to assure Indian access to broader politics.

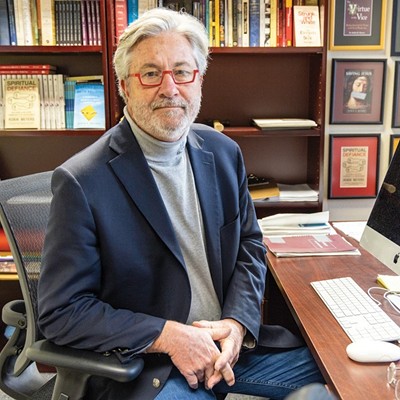

I present this as an open letter to the leaders of the American Indian tribes and nations of Oklahoma. There is a body of voting scholars who want to understand your elections, the motivations of your citizens and your leadership, in order to encourage participation in civic life outside of the governance of the tribes. - Keith Gaddie

Gaddie is a professor of political science at the University of Oklahoma and partner in TvPoll.com.

A letter to 'Indian country'

[{

"name": "Air - Ad - Leaderboard - Inline",

"insertPoint": "1/2",

"component": "10513996",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "6",

"parentWrapperClass": ""

}]