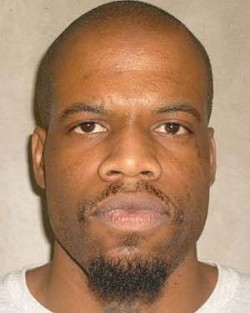

In the end, Clayton Derrell Lockett’s botched execution was still quicker and less violent than that of Stephanie Neiman, the 19-year-old girl he himself executed in 1999.

After shooting her twice, Lockett ordered a friend to bury Neiman in a shallow grave. Still alive and pleading for mercy, Neiman choked on dirt as it was thrown on top of her.

For supporters of capital punishment, and the Neiman family, Tuesday’s execution of Lockett was justice, no matter how complicated the execution process that took 40 minutes to kill Lockett.

“She was the joy of our life,” Neiman’s family said in a prepared statement following Lockett’s execution. “We are thankful this day has finally arrived and justice will finally be served.”

Minutes into the execution process, Lockett’s body began to convulse as prison officials attempted to revive him. Lockett later died of a heart attack, throwing a new wrinkle into the debate over state-sanctioned killings.

“It looked like torture,” said Dean Sanderford, an attorney for Lockett.

“His vein exploded,” Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton was quoted as saying in The Tulsa World.

Examining the protocol of injecting the three drugs used to induce Lockett’s death, Patton said, “The doctor observed the line and determined that the line had blown.”

The execution debate

Sixty percent of Americans support capital punishment, according to Gallup public opinion and research company. However, that’s a drop from a high of 80 percent in the mid 1990s, and Tuesday’s failed execution attempt in Oklahoma could intensify the spotlight on capital punishment and grow the debate about whether or not it is an appropriate form of punishment in today’s modern society.“The gap between those who support the death penalty and those who are in support of it has greatly narrowed,” said Diann Rust Tierney, executive director of the Washington D.C.-based National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. “This is a graphic picture of what the death penalty really is.”

Across the United States, 39 people were put to death in 2013, which is less than half the number from just 15 years ago. Execution verdicts have declined, and opponents of capital punishment have had some success in delaying executions with lawsuits and other legal challenges.

Despite the decline in executions and a steady rise in opponents to the practice, Oklahoma remains one of 34 states that recognize capital punishment.

Opponents have challenged the state’s use of controversial drugs and its refusal to disclose the source of those drugs administered in an execution. Lockett was momentarily successful in postponing his death before the state Supreme Court validated his execution and the practice of keeping the drug sources and manufacturers a secret.

Full examination and fallout

Tuesday’s failure gives opponents of the practice a platform to speak from, and even supporters of the practice, such as Gov. Mary Fallin, have had to admit that executions should be put on hold until more can be learned about how the state goes about killing people.

“I have asked the Department of Corrections to conduct a full review of Oklahoma’s execution procedures to determine what happened and why during this evening’s execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett,” Fallin said in a statement less than an hour after Lockett’s death. “I have issued an executive order delaying the execution of Charles Frederick Warner for 14 days to allow for that review to be completed.”

What Tuesday’s execution will mean for local politics is yet to be seen. Republican lawmakers, who hold a supermajority in the state, have been slow to comment on the incident. Considering 2014 is an election year, it’s likely the issue of capital punishment will be a talking point for candidates in the coming weeks and months. However, in a state that has executed more people than just two other states — Texas and Virginia — and has the highest rate per capita, local opposition might be slow to rise.

Broken down by party affiliation, Gallup reports that 81 percent of Republicans support capital punishment, which is a few points higher than just three years ago.

Whether or not the act of capital punishment comes under attack, the debate over the secrecy of drugs used in Oklahoma is not ending anytime soon.

“This is not about whether these two men are guilty; that is not in dispute,” said Ryan Kiesel, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Oklahoma. “Rather, it comes down to whether we trust the government enough to allow it to kill its citizens, even guilty ones, in a secret process.”

The ACLU’s legal director, Brady Henderson, said Lockett’s execution highlighted the need for the public to have access to information about the drugs used.

“If we are to have executions at all, they must not be conducted like hastily thrown-together human science experiments,” Henderson said.

In a column for The Atlantic criticizing the secrecy used by Oklahoma in administering drugs in the execution process, Andrew Cohen said Tuesday’s execution would quickly become a political issue in Oklahoma and across the nation.

“If we are to have a death penalty in this country, [Lockett] was a suitable candidate,” Cohen wrote. “But in its zeal to kill him ... Oklahoma turned him into a symbol.”