In 1990, Oklahoma’s adult obesity rate hovered around 10 percent. By 2017, that rate increased to 36.5 percent, the third highest in the country. It’s a trend that mirrors a national increase in overweight and obese citizens that projections estimate could include 75 percent of the country’s population by the next decade.

What caused the increase? There is no single smoking gun. Access to fresh food, the subsidization of corn and a reliance on heavily processed foods all play heavy hands, but it is hard to overlook the vilification of fat over sugar that still dictates opinions on what constitutes a healthy food option.

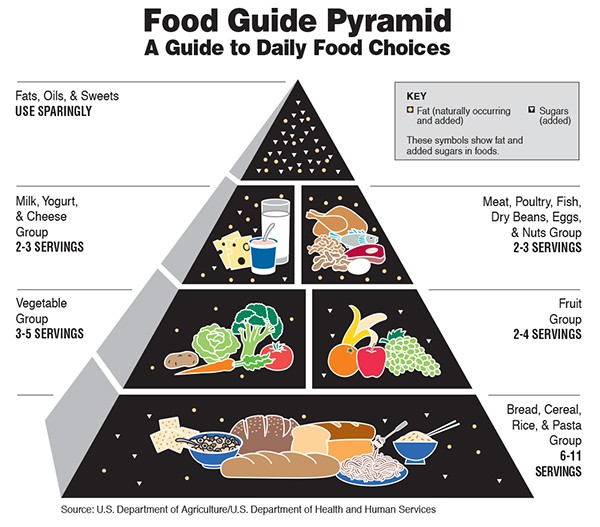

The watershed year for nutrition guidelines and crazes was 1992, and its vestiges are still felt today. The same year the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) unveiled its now-defunct and much-maligned food guide pyramid, the most popular snack item that year was the Nabisco line of SnackWell’s that promoted fat-free but high in sugar cookies and crackers as guilt-free snack options.

The original suggestion to the USDA for its food pyramid included a strong base of fruits and vegetables, but the version that was sent to the public featured the most prominent food group as simple carbohydrate-heavy bread, cereal, rice and pasta after lobbying from grain, meat and dairy industries — all of which are heavily subsidized by the USDA according to an autobiography by Luise Light, the former USDA director of dietary guidance and nutrition education research.

“The ‘Pyramid’ [originally] emphasized eating more vegetables and fruits, less meat, salt, sugary foods, bad fat and additive-rich factory foods,” Light wrote in What to Eat. “USDA censored that research-based version of the food guide and altered it to include more refined grains, meat, commercial snacks and fast foods, only releasing their revamped version 12 years after it was originally scheduled for release.”

There were reports in USA Today and The New York Times in 1992 of people chasing Nabisco trucks and bribing grocery store workers to get their hands on SnackWell’s “guilt-free” snacks, which were anchored by the devil’s food sandwich cookie. Although the cookie had zero fat, its first ingredient was (and remains to this day) sugar. A single 16-gram cookie had nine grams of sugar in 1992. The amount of sugar has been reduced to 5 grams in recent years as SnackWell’s current owner B&G Foods removed high-fructose corn syrup and other additives.

SnackWell’s boom didn’t last long. By 1998, Nabisco was already reformulating its product to add fat to certain SnackWell’s products in attempt to regain market share. A New York Times story from that year on the recipe change focuses on fat as the culprit of health issues, only mentioning sugar to say that it was added to its mini chocolate cookies to sweeten the taste.

Fat shaming

The disparagement of fat over sugar dates to the 1960s, when the Sugar Research Foundation — now known as the Sugar Association — paid three Harvard University scientists to research the connection of sugar, fat and heart disease, according to research uncovered by JAMA Internal Medicine in 2016. The sugar foundation picked favorable studies to include in the final report, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 1967 and put the onus of heart disease on saturated fat while minimizing the effects of sugar.NEJM did not require financial disclosures until 1984. All three of the Harvard scientists involved in the study have died, but one of the scientists paid by the sugar industry — D. Mark Hegsted — became head of USDA, where he helped formulate the agency’s precursor to the food pyramid. Hegsted’s research suggested that sugar’s main concern was only with tooth decay.

The influence of corporate interest in food studies continues to this day. In 2015, The New York Times revealed that Coca-Cola spends millions of dollars annually to fund studies that minimize the role of sugar in heart disease. In 2016, Associated Press reported that candy makers fund studies that suggest that children who eat more candy weigh less than those who do not. According to American Heart Association, men should consume 37.5 grams of added sugar per day, and women should consume 25 grams. The average U.S. citizen consumes just over 71 grams per day.

“Many nutrition experts feel that the villainizing of fats over the past several decades is what has led to the obesity epidemic in our country,” said Dr. Tawni Holmes, professor in nutrition, dietetics and food management at University of Central Oklahoma. “When they removed fat from products, sugar was added so that they would still taste good. Anytime you have extremes in thinking — cutting one thing out completely — you get away from moderate intake with a variety [of foods], and this is when we tend to see the scales tip towards negative side effects. Sugar that’s not utilized immediately for energy gets stored as fat, which then contributes to the same cardiovascular risk factors as a high-fat diet.”

A study done by Healthline of 3,223 U.S. residents found that a majority of respondents were concerned by sugar in the diet, but two out of three struggled when it came to identify foods that are high in hidden sugar. They were as likely to choose sugary cereal over avocado toast for breakfast and assumed that a Starbucks chocolate croissant (10 grams) had more sugar than Dannon strawberry yogurt (24 grams).

Even during the fat-free craze of the ’90s, sugar and simple carbohydrates were under scrutiny. The same frenzy that led to fad diets such as Sugar Busters! and the Atkins diet can still be seen in the tenets of the Whole 30 and ketogenic diets today. Since 1959, research shows that 95 to 98 percent of attempts to lose weight fail, and two-thirds of dieters gain back more than they lost, according to Huffington Post’s “Everything You Know About Obesity Is Wrong,” by Michael Hobbes.

“Any of these fad diets will make you lose weight because you’re cutting something out,” Holmes said. “People go back to eating the way they were before because they can’t maintain that type of eating long-term because it’s not sustainable long-term or not palatable. They gain the weight back and it gets you into yo-yo dieting, which is a little bit unhealthier than if they stayed at the same weight. It’s been one side blaming the other, and in reality, if everyone ate moderate amounts of fats and carbohydrates — and the right type of them [complex carbohydrates and vegetable fats that have not gone though hydrogenation, the process that turns them into trans fat], we’d be better off. It is a constant quest for a magic cure, and we never get there because we’re cutting something out.”

Holmes recommends shopping on the outside aisles of the grocery store, where customers are less likely to find heavily processed products, and planning meals ahead of each week to cut out the reliance on eating out or cooking prepackaged meals with preservatives and high-fructose corn syrup at home. She also stressed the inclusion of a high-fiber diet. Fiber binds with saturated fat and cholesterol and prevents it from developing as arterial plaque.

“If a product has more than five ingredients — especially if you can’t pronounce many of them — it’s a good sign that there is a better option,” she said.

Holmes said that while diets that cut out entire food groups are inherently flawed, the idea that a plant-based diet has incomplete proteins is a myth and should only be a concern if you aren’t eating a variety of plant-based proteins.

“A plant-based diet can be very healthy if you’re eating a variety of foods,” she said. “Portions can be complementary in nature like rice and beans or hummus and pita, giving you all the essential amino acids you need, and there are plant foods that contain all nine essential amino acids in a single food such as soy and soy-based products like tofu, tempeh, edamame, quinoa and buckwheat.”

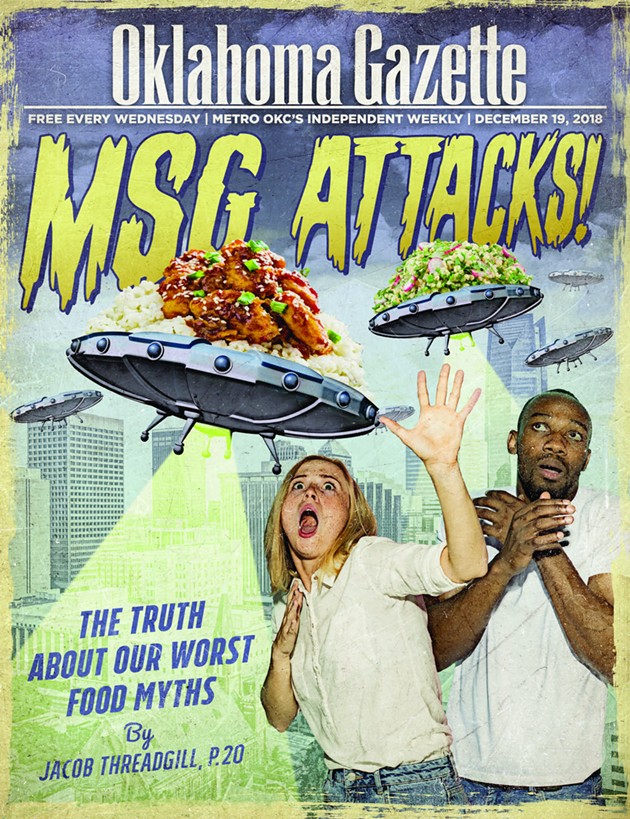

MSG lies

In 2002 — nearly a century after it was first discovered — the fifth taste, umami, was officially recognized by an academic report in Chemical Senses. The initial discovery of umami came from Tokyo professor Kikunae Ikeda while eating a bowl of dashi, a soup made from seaweed. He wondered how it contained meat flavor without the presence of meat.Ikeda, who was a chemist, found a common bond between tomatoes, cheese and asparagus — they are high in glutamic acid, a nonessential amino acid — and published findings in 1908. He renamed the acid umami because it means “delicious” or “yummy” in Japanese. He isolated the flavor in the form of monosodium glutamate [MSG], processed by the body the same way as glutamate, which naturally occurs in most food proteins.

MSG made its way to the U.S. in the 1930s, where it became a common addition to frozen and canned goods until NEJM published a letter from Chinese-American doctor Robert Ho Man Kwok, who complained of chest palpitations, headaches and joint pain after eating at Chinese restaurants and placed the blame on MSG. Kwok’s letter combined with a growing movement to remove additives from food made MSG a pariah in the restaurant and food industries.

In the intervening decades, single- and double-blind studies have failed to produce the symptoms described by Kwok under the headline “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” Chinese restaurants have taken the brunt of anti-MSG sentiment despite the fact that products like soy sauce, fermented cheese and dry-aged beef naturally have plenty of glutamate.

During a 2012 presentation at the MAD Symposium in Copenhagen, chef David Chang addressed the stigma of MSG. He talked about speaking with a customer who was insistent they added MSG in food at his Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York and complained of joint aches despite the fact that they did not.

“The same people that say they’re allergic to MSG will happily dip their sushi in soy sauce or eat a miso soup,” Chang said. “Two food ingredients that are high in MSG are Marmite and Vegemite. People are slathering their toast with Marmite, and it’s just a healthy dose of umami.”

There have been an increased number of news stories over the last few years writing off MSG as completely harmless. Even with a rash of coverage in favor of MSG, it remains the sixth most mentioned ingredient customers want to avoid according to the International Food Information Council. Over 40 percent of U.S. citizens say they don’t want to eat MSG. It is on Whole Foods Market’s banned ingredient list.

The ingredient is classified as “generally recognized as safe” by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but there is some evidence to suggest that people might be sensitive to MSG, which is led by American University professor Kathleen Holton, who has made some double-blind connections between glutamate intolerance and chronic pain, but it is considered a rare occurrence and doesn’t rise to the frenzy associated with “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

In Oklahoma City, MSG is available at international markets such as Super Cao Nguyen, 2668 N. Military Ave., but it also offers an unprocessed version made with mushroom powder and salt.