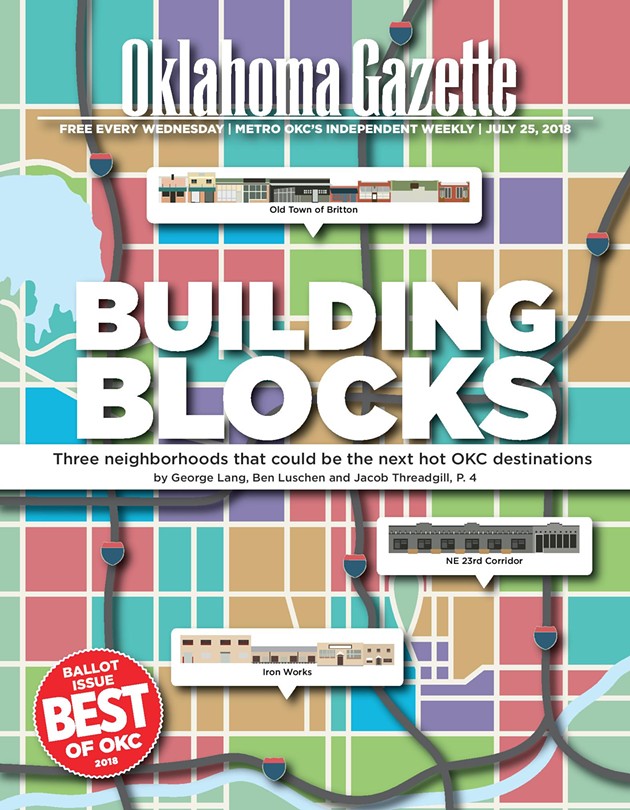

Oklahoma City’s network of thriving business districts exploded over the past two decades, building community and stoking the city’s economy in areas dominated by locally owned businesses. Neighborhoods such as The Paseo Arts District, 16th Street Plaza District, the Western Avenue District, Automobile Alley, Midtown, Bricktown, Wheeler District and Film Row have transformed from disused or neglected blocks into magnetic destinations for OKC residents.

Chances are, this is only the beginning. Nascent districts are cropping up in areas that were previously overlooked, and while these districts are in the early stages of development, signs of revival are unmistakable.

Iron giants

Like any community just moving beyond wooden buildings in the early 20th century, Oklahoma City needed infrastructure and manufacturing, and one of the key hubs at the time was centered in a few square blocks between Main Street and Linwood Boulevard west of Western Avenue. This was the home of J.B. Klein Iron and Foundry Company, which later became Robberson Steel and Bridge Company, 1535 NW Fifth St.

That business, which built many of Oklahoma’s early bridges, was surrounded by other manufacturers that required large spaces for machinery and warehousing. A century later, what recently became known as the Iron Works District contains several blocks of open spaces, many with high barrel ceilings, that make the area an ideal development spot for entertainment destinations, restaurants and retail.

Manufacturing and industry still takes place in the Iron Works District with companies like Wood Window Rescue, 1720 NW Fifth St., but the area is now attracting a different sort of creativity. Chaos, a studio where visitors can take apart and reassemble old electronics and machines into pieces of art or simply engage in creative destruction, recently opened at 1322 NW Sixth St. And 1577 Productions, a film and video production company, recently relocated to a restored office space at 1701 NW Fifth St.

David Tester founded 1577 Productions six years ago, and until recently, he and senior creative director Christopher Hunt were operating out of a small space on Film Row. However, the potential for more square footage at a reduced cost attracted the two filmmakers to the Iron Works District. He contacted Scott Smith, who operates Corsair Cattle Co. with his brother, R.D. Smith, and was a key investor in Midtown real estate in the 1980s and 1990s. Smith showed Tester the Iron Works property and the wheels started turning.

“So I told Chris about it and he came and checked it out the next day … and he loved it, too,” Tester said.

Before 1577, Hunt operated a production company called Midwest Media in the 16th Street Plaza District, and the new space reminded him of what he had when the Plaza District was emerging as a center of cool culture.

“It allowed us room to grow,” Hunt said. “I told Dave, ‘It feels like we’re moving from Manhattan to Brooklyn.’ That’s kind of what this feels like: Brooklyn in, like, 1998.”

Derrick Ott, who is working with Smith to develop spaces in the district, said there are several restaurants, breweries and retail businesses looking at Iron Works as a potential location, with some large windowed spaces being ripe for conversion to mixed-use/residential lofts. He said the industrial nature of the buildings’ past use means that the electrical systems are strong enough to accommodate any kind of modern use, from music venues to large-scale restaurant operations.

Such use was given a test on Nov. 4, 2017, when Factory Obscura mounted its Midnight Dinner, a fundraiser for its SHIFT installation, in an expansive space near 1577’s offices. Featuring aerial dancers and massive art displays, Ott said the invitation-only event offered a glimpse into the possibilities for the district.

Ott is currently working on redevelopment of Willard Elementary School, a 27,500 square-foot school building at 1400 NW Third St. that has been vacant for years.

“We’re looking at that for everything from moderate income to high-end condos,” Ott said.

He said that in a city known for being overly accommodating for vehicles, Iron Works will be a haven for bicycle and on-foot travel.

“Think of this as a pedestrian boulevard with broader sidewalks — more walkable,” Ott said. “This is one of the most walkable neighborhoods in Oklahoma City, and we’re only about four blocks from The Jones Assembly and 21c.”

Potentially great Britton

Not many remnants of the Old Town of Britton remain, but as developers have saved two of the once-independent town’s landmarks from demolition, there is a burgeoning movement to inject development into one of Oklahoma City’s “last frontiers” for economic growth.

Located between Western Avenue and what is now Broadway Extension, Britton was established in 1890 and had a population as large as 2,239 by the 1940s but began to economically flounder in the post-war era. It was annexed into Oklahoma City in 1950.

Built in the 1930s, Owl Court is a vestige of Oklahoma City’s connection to Route 66, as the motel offered clean rooms to weary motorists. A group led by Marcus Ude, Thomas Rossiter, Brad Rice, Rusty LaForge, Marc Weinmeister and Tyler Holmes purchased the property at 742 W Britton Road in 2017.

The group formed Owl Court LLC and is in the process of cleaning up the buildings. It recently applied for permits to renovate the old motel on the property’s south end, which the group hopes to convert into micro retail spaces for local businesses, Ude said.

“The project is very special to me because it’s one that was brought to life by Thomas Rossiter, one of my best friends, who is now fighting for his life after being diagnosed with brain cancer,” Ude said. “He’s always had a heart to help the community around him and sees Owl Court as a catalyst that could promote further investment and interest in a community that has been neglected for several years.”

Ude is founder and current president of Britton Business District, which became an officially recognized organization with the city in August 2017. The signs of growth are popping up slowly but surely. A Variety Care opens it doors Aug. 1 and will offer low-cost medical, dental and eye care for residents while employing 100 people across the street from Owl Court.

At Britton Business District’s monthly meeting in July held inside Marianne’s Rentals, board members and local interested business owners discussed details of the first Britton District Day that will be held Nov. 3.

Claude Hall is a resident of the Britton District and organizer of OKC and Las Vegas Gun Show. Hall also helped the Paseo in the early days of its Paseo Arts Festival, which he said now brings in $100,000 for the district annually.

“The first year is all about getting the name out, but down the road, all food and drink needs to be coordinated through the association. You sell tickets, which people then take to the vendors. You keep 15 percent and the vendor collects the rest by presenting the ticket,” Hall explained during the meeting; he is an example of experienced and interested parties helping the new district get its legs.

“We have some benefits by the fact 16th Street Plaza, Uptown [23rd] and Western Avenue districts already exist,” Ude said. “We get to reach out to those individuals that were forces and brought it to fruition.”

In addition to Owl Court, developer Andrew Hwang saved The Ritz Theater, which was a popular film house in the 1940s, in 2016. His company oversaw the installation of a new roof and complete overhaul of the building inside, removing carpet and mold.

Hwang said they’ve received several offers on the building, but no deal has been made. Potential buyers have been scared away by its lack of dedicated parking and the fact that no one wants to take a leap of faith.

“The district needs more of a reason for people to want to go there,” Hwang said. “In my opinion, it needs a major restaurant or some big driver that gets people excited. If you look at the Plaza District, the first [new] restaurant there was The Mule. A lot of people didn’t know where the Plaza District was before The Mule.”

Hwang preached patience and said he’s in no hurry to sell or lease The Ritz. He said recent development in Capitol Hill was more than 10 years in the making and noted that it took years for Plaza District to kick into high gear after Jeff and Aimee Struble bought their first property there in 2006.

Ude said that Britton’s history piques a lot of interest amongst people who remember its time as an independent town. Phoenix Vendor Mall owner Danny Scott was 5 years old and a resident of The Village when Britton incorporated into Oklahoma City.

“Britton was the closest thing to a small town that I knew,” Scott said. “I remember all of the little stores and the line outside the A&A Cafe. … I appreciate everything [Ude] has done for the Owl Court. It could turn into a jewel for all of us.”

Armory and beyond

COOP Ale Works knew it needed a new space. It just did not know where that new space would be.

Sean Mossman, the locally based brewer’s director of sales and marketing, said COOP knew several years ago that it would soon outgrow its current headquarters in southwest Oklahoma City. They were looking to move somewhere generally within the city’s newly revitalized core but did not have anything specific picked out. COOP viewed a few properties, but most of them did not fit all their needs.

Then they heard the state was making the historic 23rd Street Armory — located on NE 23rd Street near Broadway Extension — available for purchase.

“When the state put out the RFP (request for proposal) for the armory, it became an instant target for us,” Mossman said, “almost love at first sight.”

In mid-July, the Oklahoma Office of Management and Enterprise Services announced that COOP would be acquiring the building. In addition to serving as its production headquarters, COOP will also be installing a full-service restaurant, a 22-room boutique hotel, multiple event spaces and offices. The unique $20 million project is expected to be completed by fall 2020.

The armory news is one of several projects defying an old notion that Broadway serves as a development barrier dividing the city’s west side from its eastern, traditionally African-American community.

“We think this location is iconic and can be iconic after we move in and restore the building,” Mossman said. “We want this to be a place for people in Oklahoma, when friends are coming in, to say, ‘Hey, you need to go check this out while you’re there.’”

Oklahoma City Black Chamber of Commerce CEO Eran Harrill was out of town at the time of COOP’s announcement but told Oklahoma Gazette the news sounded “extremely exciting.”

The Black Chamber of Commerce has been working in partnership with Pivot Project in revitalization efforts along the NE 23rd Street Corridor, focusing particularly on its intersection with Rhode Island Avenue. The two recently completed Phase I of their plan, which was the development and opening of the new Centennial Health clinic at 1720 NE 23rd St.

Harrill said it is the first time in more than a decade that the northeast community has had its own health clinic. Centennial Health also functions as the corridor’s new cornerstone for surrounding development.

“Up until that project, there wasn’t any true economic development progress that has been happening,” he said.

Phase II of the corridor plan includes a retail area that will include several concept restaurants, a bar and some retail service businesses. Construction on the 20,000 square-foot area is expected to begin in September and should be complete by early next fall.

Pivot Project managing partner Jonathan Dodson said work on NE 23rd Street has been his firm’s hardest project to fund. The traditionally underdeveloped area lacked a lot of existing support from outside investors and sponsors.

“The reason why that area hasn’t been revitalized is not because people don’t care,” Dodson said, “but because there hasn’t been money that’s been willing to go into that area.”

He thanked partners like Farmers Bank and Citizens Bank of Edmond for their contribution to the corridor development project. He hopes part of the good in the area’s initial steps toward revitalization is the development of relationships that will spark continued growth.

Harrill said the next big step for NE 23rd Street will be its own major grocery store — something the community has badly needed. Development in the area is a delicate process that needs to fit the needs of the people it is serving.

“The concern is there has to be a deliberate focus to revitalize the area, bring economic growth that is sustainable, but at the same time not disenfranchise the community that has lived there for generations,” Harrill said.

Dodson believes their development efforts will connect those with an interest in bringing new projects with financial enablers.

“I think our genuine hope is that this project is a kick-starter,” he said. “We believe there has been historic redlining on the east side of town overall just in the last 30 or 40 years.”