A few years ago, Jason Wilson used a Christmas bonus to buy two bitcoin when the cryptocurrency was valued around $200. That initial fascination allowed him to quit his day job as a truck driver and establish L’Argent Services three years ago.

L’Argent Services facilitates local demand for bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Customers can invest smaller amounts like $100 and have that converted into a percentage of bitcoin or another cryptocurrency.

Wilson acquired a bitcoin vending machine from the Czech Republic and installed it at Coin & Gold Exchange at 7714 N. May Ave. The vending machine communicates with a back-end server and what is called a “hot wallet” to withdraw bitcoin. L’Argent Services receives a 7.5 percent transaction fee.

“The demand is such that I want to kind of turn Oklahoma into a cryptohub,” Wilson said. “We’re right in the middle of the country, and we have pretty favorable laws.”

In other places in the country, like New York, a bitlicense is required to sell bitcoin, but there are fewer restrictions in Oklahoma. Wilson registered with Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen), a bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury that monitors domestic and international money laundering.

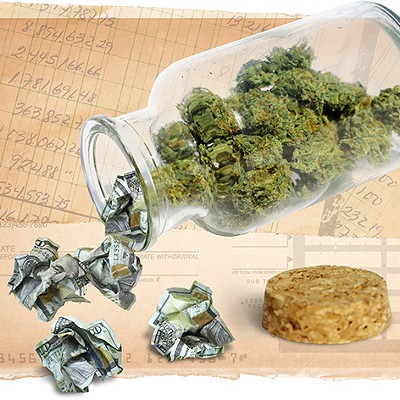

“Bitcoin has sort of lost the mystique of the dark net, but it is still used,” Wilson said. “You have to be careful that you’re not funding a drug operation through FinCen.”

Wilson deals with a variety of cryptocurrency. Some of the less popular ones are easier to access because the blockchain, the encrypted ledger that records transactions, can be created on a basic laptop.

“Bitcoin gets the headlines because it might go up to $20,000, but if you’re sitting on a bunch of coins that are worth a tenth of a penny and they go up to a penny and a half, you’ve made a huge return,” he said.

While bitcoin garners headlines calling it “digital gold,” Wilson views it as a destabilizing factor for currency the same way the internet allowed more access to information. Pre-internet, long-distance communication was costly or time-consuming.

“It’s that way for currency now,” he said. “If you have family out of the country, sending them money can be difficult, time-consuming and expensive. You can send cryptocurrency in 15 minutes, and there is no middleman.”

Wilson said he has two clients from the same village in Nigeria. The village is over 100 miles from the nearest bank, and there is only one car in the town. However, everyone in the town has access to cell phones, so they have access to bitcoin without making the trek into town.

“That’s beautiful,” he said. “It’s helping people that are unbanked and in financial crisis without a big charity.”

Origins and questions

The digital cryptocurrency bitcoin emerged in the mainstream market in 2009. Born from a detailed white paper published months earlier by a pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin was presented as an alternative to the government-controlled dollar. As a digital currency that changed hands over the internet, early adopters were mostly programmers and hackers. Next, it caught the attention of investors, traders and unscrupulous characters — those who anonymously peddled drugs and other illegal products in exchange for bitcoin. In no time at all, bitcoin had captured headlines and entered public discourse.Is bitcoin a legitimate currency? That question has been posed to Oklahoma City University economics professor Jonathan Willner more times than he can count. Intrigued college students and curious friends present their question in terms of “real money” and “not real money.”

“In reality, money is how people define it,” Willner said.

Economics students learn early in their studies that money has three attributes: It must be a unit of account, serve as a medium of exchange and store value. Under such a theory, one can present cigarettes as currency. In absence of paper money, cigarettes have served as currency, holding value and enabling transactions in prisoner-of-war camps and in the prison system.

Bitcoin doesn’t exactly fit the bill.

“Bitcoin isn’t really great money at this point because so few places will take it as transactions,” Willner said. “You can’t swap it into goods and services very easily. That makes it hard to call it money.”

Both empirical and anecdotal evidence shows that many bitcoin owners buy it, wait for it to appreciate and later exchange it for dollars. Bitcoin conversations heavily center on how much one bitcoin equals in U.S. dollars.

“You see the dollar per bitcoin,” Willner said during an interview in mid-February. “People take bitcoin and they turn it into dollars. They don’t, generally speaking, spend bitcoin. If you have bitcoin and you bought it a week ago, you spent $17,000 on a bitcoin. Today, it is only worth about $8,000. It’s lost a lot of value in the interim. It makes people reluctant to hold it.”

Willner falls into the category of bitcoin skeptics. He argues bitcoin resembles a Ponzi scheme, which is an opinion not entirely his own, as plenty have argued as much in the pages of business publications.

Even though bitcoin has captured the interest of many, bitcoin’s price has been a roller coaster lately, which has Willner questioning its staying power.

“You can see the run-up in values and then the crash in values,” Willner said, “which suggests that there are a lot of questions remaining about what it’s worth and what it will be worth in the future.”

Mining disaster?

Last month, as bitcoin was surging in both its valuation and the public’s fascination with it, a Morgan Stanley analyst named Nicholas Ashworth sounded the alarm regarding bitcoin’s energy footprint.For casual observers, the notion that bitcoin could be consuming huge amounts of electricity might sound like a joke; after all, part of its appeal is its ephemeral, internet-based existence. But it takes massive servers to keep up with bitcoin demand and process transactions, and Ashworth’s forecast was alarming to environmentalists and engineers and tantalizing for energy providers.

“If cryptocurrencies continue to appreciate, we expect global mining power consumption to increase,” Ashworth said in a note obtained by Bloomberg.

In 2017, bitcoin mining consumed 36 terawatt hours of energy. A terawatt is equal to 1 trillion watts, so bitcoin energy consumption last year was roughly equivalent to 1 trillion 30-watt light bulbs burning. Ashworth’s forecast for bitcoin consumption in 2018 is staggering — he predicted the cryptocurrency will suck up 140 terawatt hours this year. The prediction bears weight; according to Digiconomist.com, a bitcoin-centric site run by analyst Alex de Vries, 2018 has already surpassed 2017. As of Feb. 22, de Vries’ Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index puts global energy usage for the cryptocurrency at 51 terawatt hours.

“Well, it’s kind of staggering, the relative increase of it,” said Evan Lemley, assistant dean of the University of Central Oklahoma’s Department of Engineering & Physics. “If you look at what was going on a year ago, we’re talking an enormous difference — a nearly fourfold increase in a year’s time. And that’s almost totally driven by the price, hence the value of the single bitcoin was that much more, so then more mining and transactions go on.”

To put things in perspective for Oklahomans, Lemley crunched some numbers from U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Global bitcoin energy consumption in 2017 was equal to half the energy Oklahoma produced in 2016 and about 2,600 times what Oklahoma City consumes in any given year. If Ashworth’s forecast holds, bitcoin will consume twice the power that Oklahoma generates this year and 9,000 times what Oklahoma City businesses and residents consume.

“Oklahoma’s not a small consumer of energy, really,” Lemley said. “We’re kind of in the middle in the U.S. I really wanted to understand, on a relative basis, how big we’re talking, and from every angle, it’s just sort of an amazing amount of energy.”

So far, not much mining takes place in North America, though Bloomberg reports that the Canadian energy giant Hydro-Quebec is courting miners. Currently, most mining takes place in China, where energy is relatively cheap and largely unregulated. Environmental impact, particularly the production of greenhouse gases by coal-fueled power plants, is something that concerns Lemley.

“There’s a lot of historical precedent, looking back at how energy is produced in Russia and China in particular, and just how unregulated that has been and still is — no doubt about it,” he said. “A lot of power in China is coal. Keeping in mind the cumulative effects of emitting CO2, the CO2 emitted by bitcoin mining sure does not help.”

Personal investment

When Juan Moreno got his first bitcoin in 2010, they were literally giving it away.“It was basically worthless, that’s how early I was,” Moreno said. “They were giving them out just for you to download the program and start mining.”

It took several years of steadily climbing worth for bitcoin’s popularity to grow from a niche following. Moreno, 25, got interested in bitcoin eight years ago as a new way to make some additional money. He was just a teenager when he first got on board, and it was a totally new concept to him that took some trial and error. He learned a lot about bitcoin and other cryptocurrency strategies through YouTube at first, but as time progressed, he came to rely on his own, independent research.

Moreno is passionate about the earning potential of crypto investments and tries to teach others how to make money from it. He grew such a reputation among friends and in online circles that strangers started emailing him and sending him Facebook messages and friend requests for advice.

Through his experience dealing with others who use bitcoin, Moreno has come to realize that there is no such thing as a typical bitcoin owner.

“People who you think wouldn’t have crypto have crypto, like grandmas and grandpas,” he said.

Moreno did say that most crypto owners tend to be from the younger, tech-savvy generation. He views bitcoin and other crypto investments as a more exciting version of the stock market with a much cheaper entry point for young users.

“Millenials, we can’t afford to put down $5,000 on stocks,” he said. “And if we lose, we really lose it.”

As serious as Moreno is about bitcoin, not everyone who has owned bitcoin is as dedicated. Caleb Montgomery, 29, bought $100 worth of bitcoin in November 2017, around the time its worth exceeded $11,000 for the first time and its mainstream popularity was at a peak. To his joy, he made money at first and decided to invest much more into the currency — as much as $500 at one point.

“It was awesome,” Montgomery said. “I thought, ‘This is just going to go up and up and up.’”

Bitcoin’s worth rises and falls constantly throughout the day. Montgomery would check the price about every hour, and friends who owned their own would send texts cheering and cursing its fluctuations as if they were rooting for their favorite racehorse.

But soon, bitcoin’s worth began to fall. Within a month, Montgomery lost all his bitcoin profit. He sold all his bitcoin and withdrew his cash, losing about $20-$30 from his total investment. While the bitcoin market has improved since then, he realized he just was not in a secure enough financial position to risk a substantial sum of money.

Montgomery said he feels some mild regret from selling his crypto, but from the beginning, he was not into bitcoin for the long haul.

“I just thought it would be a good way to make a little extra money,” he said. “I wasn’t planning on getting rich.”

Moreno has not wavered in his commitment to bitcoin; instead, he has branched out his investments into other forms of cryptocurrency, including Litecoin, NEO and Ripple. His advice to crypto-investment beginners is to keep investments secure through downloadable wallet apps and only put up as much money as is reasonable.

“Invest what you’re able to lose,” Moreno said. “You can’t put your life savings into one thing and expect not to lose it.”

Print headline: Mining cybergold; Oklahomans are both fascinated and fearful about the rise of cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.