The sound of folded copies of The Oklahoman slapping concrete in the pre-dawn hours was once familiar, but repeated cuts to the size, coverage, advertising and distribution have left many wondering not only if they will receive their newspaper that day but whether there soon will no longer be a daily newspaper at all.

Mary Mendus has subscribed to The Oklahoman for about a decade, but recent service quality made her cancel. Mendus said the service was good before around March. In fact, because she has to use a cane, her last carrier would bring the paper up to her porch.

However, a few months ago, Mendus said, “They just stopped delivering it.” When she called to complain, she said they told her she would get replacement copies, which also did not arrive.

“Then I call back and talk to somebody, and they just say, ‘Well, we don’t have enough carriers. We’re trying to find people to service this route.’ So that’s been the story,” Mendus said. “The paper’s not there, I call and put it on their automated system because that’s what they like. Then I call back again later to talk to them and say, ‘Please try to get the paper out to me.’ I really haven’t been getting it at all; the only day I got it [two weeks ago] was Thursday.”

Citing a loss of money on certain routes, the newspaper reduced its circulation area drastically Jan. 1, leading to 7,000 subscribers losing their home delivery service. It also reduced retail sales of newspapers by about 3,500 and removed all its vending machines from across the state.

“I asked, ‘Are you trying to stop delivery?’ And they said, ‘No, we’re not trying to stop home delivery.’ But I think that’s what they’re doing,” Mendus said. “The thing is, when you call and talk to somebody, you have to wait for 15 minutes sometimes. So I know that there’s a big problem because you have to wait so long, and it doesn’t do any good. It’s like beating a dead horse.”

Customer service representatives promise Mendus a credit for each day she goes without a paper, but she said that does not address the main issue.

“That doesn’t mean anything because they take it out of my checking account, and recently, they changed their arrangement,” she said. “They’re taking it out weekly instead of monthly, and they increased the rate.”

Shelly Scovill, who said she has been subscribed to the print publication “forever,” has also had issues with paper delivery and customer service. She contacts representatives who she said note her information but take no action.

“It’s just, ‘We’re sorry. We don’t know. Maybe their car broke down. We’ll get a paper to you,’ and then you don’t get one,” she said. “I’m getting the impression that [customer service representatives] are bankrupt of any kind of power to do anything. … In the past, if our carrier did not deliver the paper to door, their manager would come and deliver it. Then the actual delivery person would get that deducted from their pay, so they would be very diligent about not missing the next day.”

Scovill has had to call about not receiving a paper at least twice a week for several months. It became the norm in her household and even her Village neighborhood to ask, “Did you get the paper?”

“I’ve had neighbors tell me that they’ve talked to people in other parts of the town like Nichols Hills, and they too are getting the same message that they cannot keep carriers, that the carriers just quit,” she said. “Also the fact that they’re bringing their paper in from Tulsa has an impact on whether we get the paper or not. What the consensus is, they’re going to quit delivering the paper to our doorstep, which we all kind of know is an archaic ritual, but they just need to say it. Just say it. … They’re still saying, ‘Subscribe,’ and they got all these people that are advertising in The Oklahoman, expecting people to see their advertisements, and they’re not being seen. If I were Dillard’s or somebody like that, I’d be angry that my advertisements were not being seen as they were promised.”

She said the only reason she has not unsubscribed is because she gets a highly discounted family rate from when her daughter-in-law worked for the newspaper. However, her daughter-in-law has not worked there in about 10 years, so she is unsure why she still receives the rate.

“I really haven’t been getting it at all; the only day I got it [two weeks ago] was Thursday.” — Mary Mendus

tweet this

“If I was paying the rate that my neighbors are, I would have canceled my subscription,” Scovill said. “I pay $40 a year. I don’t know why I pay $40 a year, but I’ve talked to my neighbors and they pay $300 a year. … If the rate were to go up, I would not subscribe.”

Scovill said some people call the newspaper a pamphlet because of its reduction in size, which she attributes to GateHouse Media, the company that bought The Oklahoman last October.

“I’ve also noticed that the business pages, which is the part I like to read, has gotten less and less. It’s like down to a page or a half a page, and it doesn’t have stories in it that were pertinent and interesting,” Scovill said. “Of course, you can find some of that stuff online, that information, but we paid for a document that is supposed to be right there in your hands so you can read it. I’ll have to get on the computer. … Everybody’s coming to the realization that as much as we didn’t like the Gaylords, at least they were local.”

Despite the issues she has dealt with for months, Mendus did not decide to cancel until last week. She still enjoyed reading local stories and columns when she would receive the paper, but she also thinks the content has suffered in the past few months.

“They reduced the paper in size to where the sports and business pages are in the same section and there’s usually four or five pages. They don’t print editorials anymore; they just have editorials one day a week,” she said. “And since GateHouse Media bought the paper, all the editorials are from the conservative side; we don’t get any liberal side.”

Shrinking workforce

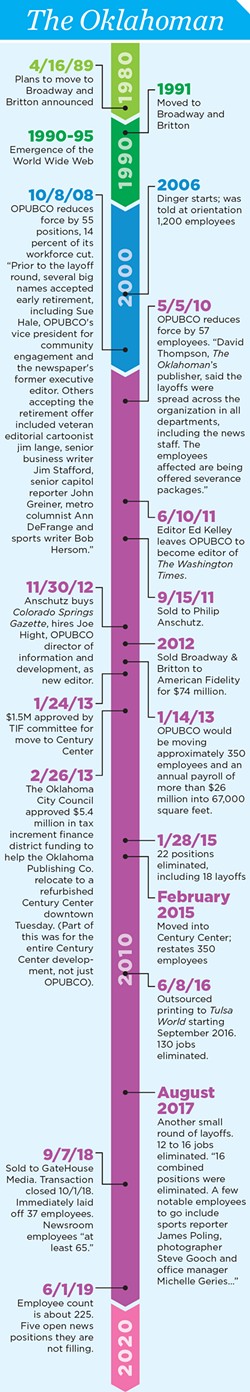

It is no surprise that The Oklahoman’s content is dwindling when juxtaposed with the rapid evaporation of the company’s personnel.Less than 15 years ago, The Oklahoma Publishing Company (OPUBCO) boasted of being a company with roughly 1,200 employees. By current count, it now employs about 225 people, said Kelly Dyer Fry, editor and publisher of The Oklahoman.

This number includes approximately two dozen people who work for the company’s marketing arm, BigWing.

BigWing was the last in a series of ventures launched in hopes of generating revenue while the print product was declining. Former publisher Chris Reen headed up another such project, an online event calendar known as Wimgo, that Philip Anschutz shuttered soon after purchasing the company.

The project launched February 2008 and was ended in December 2011. A handful of its staff were laid off weeks before Christmas, and others reintegrated back into the newspaper. Reen was tapped that summer to succeed retiring publisher David Thompson.

By the time Anschutz purchased the paper, such layoffs were becoming routine.

The first major reduction in force signaling the shape of things to come occurred in October 2008. Employees were warned that it was coming, and longtime employees were offered buyout packages. While 57 employees took early retirement, the company excised another 100 employees, which at that time constituted a 14 percent reduction in its workforce, former vice president of human resources Scott Briggs told Oklahoma Gazette at the time.

That trend continued for well over a decade. Another 57 people lost their jobs in May 2010, and smaller layoffs became a regular part of working for the company. By the time Anschutz relocated the company to the former Century Mall in downtown Oklahoma City, it had been whittled down to about 350 employees in February 2015, according to OPUBCO’s own numbers.

The layoffs continued through Anschutz’s ownership period and at the time of the sale to GateHouse in September 2018. On the day the sale was announced, several dozen people — including the managing editor, news director and several holding leadership positions — were immediately let go. They were notified via email.

Since, GateHouse has quietly made cuts, consolidating departments and closing open positions. An online job ad placed for a publisher was quietly removed and current editor Kelly Dyer Fry instead was given the second mantle.

“I had to apply for it. They posted the job on LinkedIn, and I brushed off my resume after being here for 25 years and I applied for the job,” Fry said. “As far as being publisher, I’ve always been involved on the business side of it, and so it wasn’t a huge learning curve. But I personally wanted to do it because I care more about this city than somebody who might just move in here to be a random publisher. I care about what goes on here, and I care about the people who work here.”

She said the number of reporters, photographers and editors for both the newspaper and website is 65 people.

A former newsroom employee who spoke to Oklahoma Gazette on the condition of anonymity described the possibility of layoffs hanging over the newsroom before eventually being laid off after more than 20 years with The Oklahoman.

“You would feel that little bit of relief after you were spared, and then months would go by and you knew another was coming, and it would build and build and build,” the former staffer said. “The dread would build. It was like walking on ice.”

After each round of layoffs, a sense of loss filled the newsroom.

“People who’d given their entire lives, raised families, had been at the old building and the new building were just suddenly not there anymore, and they [had] such a presence and [were] somebody you looked forward to seeing and working with and laughed with,” the worker said, adding that every three to six months, it was like “a funeral.”

And each layoff meant that the remaining staff would inherit the work of their former colleagues.

“Yeah, the pages that we had to produce just piled up and more people took on more responsibilities,” the former newsroom staffer said. “It became a slog, just a hard slog. Fewer people, same amount of pages, same amount of beats to cover. It was daunting.”

Layoffs left remaining journalists with the feeling that stories weren’t getting the proper amount of time, the staffer said.

Former staff writer Brianna Bailey left the paper to work for The Frontier, an online investigative news agency, but supports the newspaper.

“Oklahoma City needs a daily newspaper, and I’m pulling for them. I subscribe. I am a subscriber,” she said. “I think the people who are still there are doing the very best they can with limited resources. I don’t want to see them fail.”

The number of employees diminished so rapidly that a full quadrant of the building the company moved into in February 2015 is a virtual ghost town. That 21,000 square-foot portion of the building was put up for lease on July 1. Subletting that space would generate about $500,000 in revenue each year, according to a LoopNet listing.

On May 21, The Oklahoman retired its longtime web domain NewsOK. Originally a joint venture between OPUBCO and Griffin Communications, the parent company of News9, NewsOK was purchased outright in March 2007.

The new domain, oklahoman.com, was previously launched as a subscriber-only portal. In late June, an apparent paywall was implemented, though users have noted that they can still browse additional content by clearing browser caches or using incognito web browsers.

Fry said the paywall is already paying off.

“We’ve grown a lot of digital subscriptions just within the last few weeks, so that has been a bright spot for us,” she said.

Since instituting the paywall, Fry said, the number of new subscribers each week has doubled.

The print product has also announced a fee for one of its long-standing reader services that was previously provided free of charge. Short death notices — not to be confused with obituaries, which were always paid content — will now cost $25 per listing.

It is not just full-time personnel that the company cannot retain. Since GateHouse took over the newspaper and began changing its circulation procedures, there has been a shortfall in delivery drivers. Delivery issues are nothing new for The Oklahoman. Since it outsourced its printing to Tulsa World in June 2016 and dismantled the presses while eliminating about 130 jobs, deadlines were earlier and deliveries were later, meaning readers received stale news later than it had been even months prior.

In an editorial published June 2 by Fry, she wrote, “As our economy has strengthened, we find fewer and fewer people want to deliver newspapers in the wee hours of the morning, seven days a week. We currently have 45 open delivery routes.”

But according to independent contractors who have left reviews on Indeed.com, it is the internal economics and mismanagement by the company and not the economy writ large that are responsible for the poor delivery service.

“You have from 3-6:30 to deliver the number of papers you have on your list. This is a 7-day-a-week job with no days off and no calling in. You have to show up or you are responsible for finding your sub. The pay is not good, you get paid about 10 cents per paper you deliver yet if one person calls to complain about you they take $3 out of your check,” one reviewer wrote in December.

“We have been struggling to get paid for our first month. Because of the new system setup and change overs it has caused us to have two late fees on our rent and our rent’s due and we are being threatened to be kicked out of our house,” another wrote in March.

The situation has apparently not improved, according to a review left on July 2.

“Poor poor management, inconsistent hours, low pay, no days off, no support system...you’re simply out there on your own. This company changes the rules as they go. ...Whatever works for them. Run and don’t look back!!!” the reviewer wrote.

Fry said the newspaper is still having problem staffing the routes but has not seen those reviews.

“I’m not privy to any major concerns,” she said. “We changed some distribution centers, and that may have caused some people to not want to have to invest the time to drive further to pick up the route. But as far as pay, we’ve offered bonuses; we’ve offered sign-on programs. I mean, we’ve done direct mail. I mean, we’ve just done about everything you can think of as far as trying to raise their pay.”

While Fry said The Oklahoman is working “every single day” to recruit carriers, there are challenges.

“When the economy improves, throwing newspapers in the wee hours of the morning becomes less desirable in the long list of jobs that people are seeking,” she said. “And we have tried everything we can to do to recruit carriers. And we’re just having a hard time finding people who want to throw the newspaper. It’s like you fill them one day and then somebody else leaves another day. It’s always a constant struggle, and that’s not just us here, but all newspapers have troubles like this when the economy improves. We’re not experiencing anything here that everybody else in the country isn’t experiencing. You know, newspapers are challenged, and we’re giving the best we can to give our local community, the coverage that that we believe they deserve.”

Fry said any indication that The Oklahoman does not care about the printed newspaper anymore is “100 percent false.”

“The reading population has changed. I don’t know if you’re going to convince millennials to let us, you know, bring them the newspaper every day, but we might convince them to take a digital subscription,” Fry said. “I mean, people don’t understand that what’s really at stake here is beat journalism. I mean, beat journalism is very important. You know, we’re often the only media at a lot of public meetings, and we believe that that’s important, to serve as a strong journalists in our community, because we care about our community.”

Fry did not have subscriber numbers immediately available but said that while the number of print subscribers have fallen, The Oklahoman reaches more people now through its digital coverage than ever before.

“I just hope Oklahomans will support local journalism across the board,” she said. “I think it’s important.”

Mergers and acquisitions

Long before its purchase of The Oklahoman, GateHouse, which is run by parent company New Media Investment Group, built a reputation on acquisition sprees, paired with drastic cost-cutting measures that left many newsrooms bare-boned.GateHouse, which did not return a request for comment, is the largest newspaper chain in the United States, operating in 615 markets in 39 states. GateHouse also is synonymous with a decadeslong shift toward corporatization of the journalism industry.

In 1933, 63 national and regional chains controlled 37 percent of daily circulation across the country. Now, the 25 companies that own the most papers in the country are responsible for circulation of two-thirds of the nation’s dailies and a fourth of all weeklies, according to a study from Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

GateHouse is one of the most aggressive chains when it comes to pursuing new properties. Since 2013, when the company filed for bankruptcy with a listed debt of $1.2 billion, GateHouse spent $1 billion on acquisitions. About 40 percent of its papers have historically been in rural or low-income areas, but beginning three years ago, GateHouse made a foray into larger metros, with purchases in Oklahoma City; Austin, Texas; Columbus, Ohio; and Palm Beach, Florida.

Despite these acquisitions, New Media Investment Group’s stock fell from $25 a share in 2015 to its current share price of about $9. In the first quarter of 2019, New Media Investment Group reported a $9.4 million loss.

Like many newspaper chains, GateHouse also has a reputation for harsh layoffs. The company faced about 60 layoffs early this year and about 200 in May – cuts that New Media Investment Group CEO Mike Reed called “immaterial.” After the May layoffs, The Wall Street Journal reported that GateHouse and Gannett Co., Inc., another newspaper chain behemoth, held merger talks.

Across its media properties, GateHouse has embraced cost-saving measures like regional printing and design centers. News industry analyst Ken Doctor also said that GateHouse is deemphasizing its focus on print and putting resources behind growing digital subscriptions to draw in younger readers.

“The problem with that is if you cut too much out of that print product, you’re going to further that downward spiral of print,” he said. “In other words, more people will cancel (their subscriptions), and that cuts off a very lucrative revenue stream.”

GateHouse’s other tactics for increasing revenue, specifically events and digital marketing services, are not as effective in small markets, where the company has killed and consolidated papers in recent years.

“The paper has become essentially a shell of what it was, and it’s become a joke among former readers who at one time valued the product.” — Jon Mark Beilue

tweet this

In 2018, GateHouse shut down five small Arkansas papers and Daily Guide in Waynesville, Missouri.

Natalie Sanders worked at Daily Guide for eight years before quitting, in part, because of burnout. During one six-month stretch, she served as editor of Daily Guide and another area GateHouse paper, St. James Leader-Journal, which ceased publication in 2016.

When Sanders first came to Daily Guide, she said it had a total staff of 15, but when she left last year, she was one of two employees. The other remaining staffer quit at the same time, and several months later, GateHouse shut down the newspaper.

“It felt a little bit like an old friend had died because that was all I wanted for a long time was to be the editor of that paper,” Sanders said. “And I loved it. It was my community newspaper.”

In June, GateHouse consolidated 50 Massachusetts weeklies down to 18. On a smaller scale, Sanders said that GateHouse consolidated several papers in Missouri.

Another paper on the precipice of consolidation is Amarillo Globe-News in Texas, which GateHouse bought in 2017. GateHouse merged three major positions — publisher, editor and editorial page director — between Globe-News and its GateHouse-owned sister paper, Lubbock Avalanche Journal, about two hours away from Amarillo.

Jon Mark Beilue, who retired last year after 37 years as a journalist at Globe-News, said that during the last 15 months, eight newsroom staffers left and only one was replaced. For an idea of the impact this staffing shortfall had on content, Globe-News no longer includes Friday night high school football stories in the Saturday paper, despite the Texas Panhandle’s strong tradition with the sport, and has begun running press releases as bylined stories. As it is, Globe News struggles to cover a city with a population of about 200,000 with just two news reporters and one sports reporter.

“I think everyone in this industry understands what the industry as a whole is going through, with the loss of advertising revenue, with the way consumers changed the way they receive their news,” Beilue said. “But for Amarillo, [the cuts] have been drastic, draconian and they have just sapped the resources to be anything viable, anything relevant. The paper has become essentially a shell of what it was, and it’s become a joke among former readers who at one time valued the product.”

Fry said GateHouse is committed to local journalism.

“Their CEO really cares about journalism, and it’s a tough business,” Fry said. “As long as I’ve been over the newsroom, I have tried to protect our most serious journalism. We kept cuts around the edges of our investigative journalism. We don’t cut that. We haven’t cut some of our strong beat journalism because I think that’s important to our city and to the health of our democracy.”

Paper of record

From May 24 through June 24, Oklahoma Gazette looked through 32 issues of The Oklahoman to find the percentage of local coverage versus national coverage or wire reports. Only in nine issues did local bylines outweigh national bylines or wire reports. The highest discrepancy was June 24 with about 37 percent local bylines and 62.8 percent national bylines or wire reports. The average distribution was 48 percent local and 52 percent non-local.Local coverage includes not only reporting by The Oklahoman but also Tulsa World and Oklahoma Watch stories.

Four of the 32 issues — or 12.5 percent — also included BrandInsight content, which is content sponsored by local organizations and companies. BrandInsight content ranged from a third to half a page from NewView Oklahoma, Renuva Back & Pain Centers and Epic Charter Schools.

In the more traditional realm of display advertising, the news is not any better. Oklahoma Gazette analyzed the Sunday, June 16 issue of The Oklahoman for ad content. The bulk of advertising could be found in pages A1-18, which featured 5.9 pages worth of ads, including over two pages of house ads (ads for The Oklahoman or one of its products) or ads for events or activities sponsored by The Oklahoman. Section B, the sports section, featured no advertising, as was the case with the Digital Extra section featuring wire copy from GateHouse. The 12-page TV Week supplement featured one full-page house ad on the back page. All told, the 72-page issue featured just over 11 pages worth of ads, not counting classifieds, or 15 percent of the total page count. When house ads were factored out, just over 6.5 pages (9 percent) of revenue-generating ads appeared in the issue.

For longtime subscribers, the shrinking paper, inadequate delivery and poor customer service means weighing whether or not to cancel a subscription that has been part of their families for generations.

“I’m starting to realize that they are not essential, and it’s hard for me, being a longtime Oklahoma citizen, to give this up. My husband said we might as well be subscribing to USA Today or something like that … because the lack of local news,” Scovill said. “We look at the obituaries. It’s the main thing we like to look at and some other local things, but people are starting not to put their things in The Oklahoman because it costs too much.”

Mendus, who is considering a digital subscription despite the fact that it does not include everything she would like to read, said she cannot imagine what her mother would do if she did not receive the newspaper.

“It’s less and less essential; it really is. I really do like to have the local news — I like to read about the local business news and just the local news — but I’m not gonna get that anymore,” Mendus said. “I may subscribe to the online newspaper depending on how much it costs; I’m sure not going to pay over $30 a month for it. I may switch to that, but I won’t get the bridge column.”

Editor’s note: Matt Dinger and George Lang are former employees of The Oklahoman. Mollie Bryant, editor of news nonprofit Big If True, contributed reporting on GateHouse. This piece was produced as a partnership between Oklahoma Gazette and Big If True.