Oklahoma City’s African-American children face a reality in which they will be underrepresented in postsecondary education and overrepresented in prison.

“It’s sad, isn’t it?” said Valerie Thompson, president of Urban League of Greater Oklahoma City.

Indeed, 9 percent of students enrolled in Oklahoma public colleges are black, according to data from State Regents for Higher Education. Also, the latest numbers from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections shows that 28 percent of the state’s inmates are black.

The inequality between children of color and their white, more affluent classmates is well researched and documented both locally and across the country.

Even when compared to national research that shows ethnic students who live in poverty and attend urban schools often score lower in nearly every education, income, health and incarceration benchmark, OKC’s and the state’s rankings regarding black students expose a grim picture.

For an African-American, Oklahoma City offers few opportunities to improve income mobility or achieve academic success.

Suspension judgment

Even from birth and into their grade-school years, research shows that African-American children face hardships and challenges that affect them well into adulthood.“It’s alarming,” Oklahoma City Public Schools Superintendent Rob Neu said last year in reaction to a report from The Center for Civil Rights Remedies.

The study revealed that OKC public schools suspend more black males than any other public school district in the nation.

Oklahoma City Community College’s Planning and Research Department recently told the OKC school board that suspension is a key indicator of challenges that might follow for a student, including raising the possibility of dropping out of school and reducing access opportunities for post-high school education.

Other top indicators of restricted income and social mobility opportunities include poverty and school absences. District data shows that black students experience both at higher rates than other ethnic groups.

Neu has said there are ways to improve how — and how often — local black students are disciplined. He also invited several outside firms to gather and examine student-level data in order to identify problem teaching and learning areas and develop new problem-solving strategies that are specific to the district’s needs.

Thompson agrees with Neu’s approach.

“I think part of the solution is having teachers and school officials who are trained on what some of those issues are in [the African-American] community,” Thompson said. “Being aware that we have an issue is the first step, but the schools also have to have resources they can use. I think [Oklahoma City] schools understand that.”

Financial barricade

Thompson said poverty drastically impacts children and families of all ethnicities and poverty rates in our city’s African-American community are higher than the national average.“There is a cycle of poverty,” Thompson said. “A lot of these kids don’t have the same opportunities that you would find in more affluent schools or communities.”

Education is a critical part of a child’s life, especially in the local black community, because options for those who become involved in any criminal activity or fail to earn a degree can be further limited as a student reaches adulthood.

Young black adults who lack a high school degree or job training face a stark probability, said Jermaine Simpson, employment and training program director at Urban League of Greater Oklahoma City.

“It’s pretty much guaranteed they are going to go back into the [prison] system,” Simpson said.

In two years, the program that Simpson oversees has worked with nearly 200 18- to 24-year-olds who lack high school degrees or have criminal records. Out of that 200, around 70 are now employed, 12 are enrolled in a full-time university and 41 have job certification.

“Most of the kids who come into this program are coming from less privileged households, so the options after school, including just dreaming about a better life, are very limited,” Simpson said. “Growing up in this community, many of these kids feel like they don’t have any options, and Oklahoma City schools don’t really promote secondary education to a lot of these kids.”

Earning power

Family income levels influence education outcomes, and when data shows that Oklahoma’s African-American children often face higher poverty rates, it might be no surprise that many of these students do not reach academic benchmarks.Forty-four percent of the state’s black school-age children live in poverty, compared to 17 percent rate of white children, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty.

That 27 percent gap is the fourteenth highest in the nation.

However, there are two key statistics that also indicate poverty isn’t the sole hardship that hinders many black youth from receiving a better education.

First, 60 percent of all OKC students living in poverty can read at their grade level in third grade, district data shows. However, only 49 percent of third-grade black students read at grade level, regardless of their economic status.

“Current academic performance data tells us there is something more important than poverty ... that is influencing our African-American students’ ability to thrive,” Neu said.

The Learner First, a Seattle-based education consulting firm that is working with the district, found a similar theme in other subjects.

“A lot of people would say that the reason African-Americans aren’t doing well in math, for example, is that a lot of them are living in poverty and there are factors in their home and community environment that are impacting their ability to achieve,” Jane Davidson, a consultant with The Learner First, said last year in an interview with Oklahoma Gazette. “Well, if that’s the case, then kids on free and reduced lunches, kids who are living below the poverty line, should be doing worse than African-American kids, because some of those African-American kids are not living below the poverty line. But the reverse was true.”

The school district’s goal is to find out what other issues negatively impact their learning experience so they can help address them.

Blacks comprise more than 80 percent of student enrollment at seven district schools: Edwards Elementary School, Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary, Thelma R. Parks Elementary School, Frederick A. Douglass Mid-High School, Northeast Enterprise Mid-High, Harper Academy Charter School and Stanley Hupfeld Academy at Western Village. In the three ZIP codes feeding those schools, the average adjusted gross income is $23,419, which is $17,826 less than the state average, according to the most recently available income tax return data.

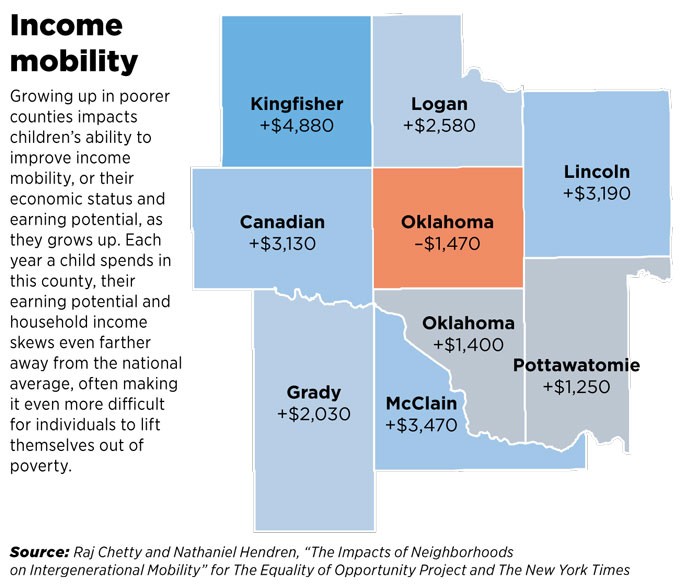

Some studies indicate that growing up poor in Oklahoma City is more detrimental to children’s futures than it would be if they grew up with the same economic hardship in neighboring communities.

The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility study shows that geography plays an important role in children’s income earning ability as they enter adulthood and finds that moving from OKC to a neighboring suburb like Yukon or Mustang increases their lifelong earning potential.

Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, the two Harvard economists who authored the study, compared the earning potential of poor children based on which county lived in.

Research shows that, on average, poor children growing up in Oklahoma County will earn $1,470 less per year in adulthood compared to the national average of other poor children.

Further, the study indicates that earning potential improved by $4,600 a year for children who grew up with similar economic challenges in Canadian County.

The study also asserts that Oklahoma County is one of the worst places for children when it comes to breaking the cycle of poverty, no matter the race or ethnicity.

“Our findings provide support for policies that reduce segregation and concentrated poverty in cities (e.g., affordable housing subsidies or changes in zoning laws) as well as efforts to improve public schools,” wrote Chetty in a review of his study. “The broader lesson of our analysis is that social mobility should be tackled at a local level by improving childhood environments.”That is why John Thompson, an OKC-based education writer and former inner-city teacher, believes education levels among poor children will never show drastic improvement without policy changes that are also made outside of school walls.

“[Some] school reform is based on the idea that you can ignore adverse childhood situations by just having high expectations in the school,” Thompson said. “But most problems faced by a child in school are interconnected with the outside world ... and we have to address all of the interconnected problems together. Number one has to be early investments in healthcare, prenatal care [and] healthy living.”

Oklahoma ranks in the top five nationally for its high number of stroke deaths, heart disease and diabetes, according to the Oklahoma State Department of Health. Health outcomes for the state’s African-American population are even more problematic.

Infant mortality among Oklahoma African-Americans is 13.7 per 1,000 — nearly twice the rate of Hispanic and white residents. Blacks also have higher rates of cancer, stroke and diabetes than whites. However, rates of fruit consumption, smoking and physical activity are similar for both blacks and whites in Oklahoma.

Schools can require children to take physical education courses, but they are not involved in policy and infrastructure decisions as they relate to promoting healthy lifestyles outside of classrooms.

“There’s been a lot of research that shows us there is [a] very clear correlation between educational attainment and health and wellness,” said Gary Cox, Oklahoma City-County Health Department executive director.

He said the agency hopes to build a health and wellness center in south OKC next to Parmelee Elementary School, which would be similar to one located near Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary in the northeast.

The health department also offers physical education programs to local schools.

Community involvement

In April, parents gathered at Frederick A. Douglass Mid-High School for a forum that was hosted by the local (PTA). State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister addressed the community, as did state lawmakers from northeast Oklahoma City.“Between the two (Tulsa and Oklahoma City), you may have 20 to 25 urban legislators,” said Rep. George Young, D-OKC. “All the rest of them ... are ranchers and farmers. They don’t get what we go through. They can’t speak for us.”

Young’s remarks came after several lawmakers said that northeast Oklahoma City — home to the city’s largest African-American population — must do more to improve its schools because solutions likely wouldn’t come from the city or state.

Their voices echoed the results of a survey conducted last year by the city’s Strong Neighborhoods Initiative. It found that 67 percent of northeast residents believe the quality of education in northeast OKC is not equal to that in other areas of the city.

“The community has known this has been an issue for quite some time, and we [at the district] have to be honest about it,” Neu said of the survey results. “We are taking on this issue because if we fix this cultural issue ... you are going to see a significant change in the achievement levels.”

During the forum, Rep. Mike Shelton, D-OKC, another northeast lawmaker, also reiterated the need for community involvement.

“We are going to have to get some help [for our schools], and it’s going to have to come from the people who live in this community,” he said.Increased attendance at PTA forums like this one and improved voter participation were suggested, as was considering the addition of more charter schools.

OKC district enrollment data shows approximately 13 percent of African-American students attend charter schools, and with the success at some of charter schools, parents and lawmakers at the forum expressed interest in finding ways to increase that number.

In 2014, the average state-ranked grade for the seven schools with more than 80 percent black enrollment was 54.1, which translates to an F letter grade.

However, during the same time period, Stanley Hupfeld Academy at Western Village, a charter school with a black student enrollment of 80 percent, had a state grade of 70 percent. Similarly, KIPP Reach College Preparatory, a charter with black enrollment at 78 percent, scored a 91, one of the highest in the district.

Half of the district’s charter schools are located in the northeast side. Earlier this year, the school board rejected a Lighthouse Academies application that could establish a charter school in that area.

However, the application was later approved after Lighthouse agreed to locate the school on the south side, where the district is experiencing overcrowding.

School board member Ruth Veales, who represents northeast schools, said district leadership told her the Lighthouse decision did not mean other northeast charter applications would be denied.

Amber England, executive director for Stand for Children Oklahoma, an education advocacy group that promotes parental empowerment in the district, is hopeful.

“I think parents are in the mindset right now that it’s up to us,” she said, “and charters can be a way to do that.”

As a middle school, KIPP draws students from elementaries like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Thelma Parks.

“We are a charter school that is designed to get our kids to and through college,” said Tracy McDaniel, KIPP’s principal.

McDaniel said KIPP increased daily instruction time for math and reading. It also studies data to help identify problems and works with students into high school and college.

KIPP is a high-minority and high-poverty school — 80 percent of students participate in free or reduced lunch programs.

“Our teachers, administrators and our secretaries, we are all counselors too,” McDaniel said. “We are … teaching kids that no matter what is going on in their life, you have to finish your work.”

Success studies

Charter critics say the schools remove high-performing students from traditional public schools just as they’re developing ways to improve education opportunities and results for their black students.FD Moon Elementary Academy, a northeast school with black enrollment at 77 percent, is viewed as an F school by the state with low marks in math and reading. However, initial results from its Summer STEAM Academy, launched last summer, show growth. As a partnership between SNI and the district, its curricula focuses on STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and math) and aggressive reading intervention.

Students were tested before and after the four-week summer program, and results showed improvements in reading and math scores for every grade, including a 29 percent increase in sixth-grade reading levels and a 43 percent improvement in first-grade math scores.

“The best part of this is we can see that it’s working,” said Shannon Entz, an SNI senior planner.

Collaborating with the city and other organizations and acknowledging and adapting for cultural, health and economic issues, developing solutions and intensive, individual-focused student programs can improve long-term economic and social mobility in largely underserved African-American communities.

“Its a systemic problem that we have had here in Oklahoma City for many years,” Thompson said. “The first thing we have to do is admit we have a problem and then be committed to finding a solution.”

For the transformation to happen, city and school leaders agree that there must be a collaborative effort between agencies.

Neu, who is completing his first year as OKC superintendent, has said African-American achievement is a primary, critical issue and many solutions can be found by partnering with the community and working with students on an individual level.

He also spoke about improving the relationship with the minority community.

Print headline: Warning bells, With odds stacked against many of OKC’s black students, what can be done to increase academic performance and economic mobility while reducing dramatically high discipline rates?