Before there was Magdiel Sanchez, a deaf Hispanic man shot and killed by Oklahoma City police last month, there was Pearl Pearson, a deaf motorist accused of fighting Oklahoma Highway Patrol during a traffic stop. Decades before, there was George Kiddy, a deaf man who sat two days in Oklahoma City jail on a public drunkenness charge and was denied an interpreter.

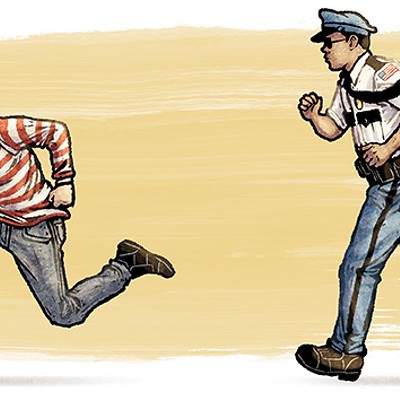

Well known to the state’s deaf and hard-of-hearing community, these stories of deaf citizens’ interactions with police highlight the lack of training and awareness around communicating with the deaf. The fear of miscommunication with law enforcement resulting in police brutality looms in the community, explained Renee’ Sites, who is deaf and serves as president of the Oklahoma Association of the Deaf.

“Social injustices are real,” Sites wrote in an email interview with Oklahoma Gazette, “and it has been for a long time for the deaf community.”

While the Americans with Disabilities Act calls for officers to take appropriate steps to communicate effectively with the deaf, the latest tragedy calls into question local officer training. In the days since the officer-involved shooting in southeast Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Association of the Deaf — an organization committed to promoting, protecting and preserving the civil rights and quality of life for the deaf — has launched a campaign to strengthen the police training they believe is lacking.

“We want to be heard,” Sites wrote. “And we want officers to know that not all of us are the same. We are a very diverse group of deaf individuals from all walks of life. All law enforcement should receive specified training specifically on deaf and hard of hearing individuals, and that training should be given by deaf individuals, not by anyone hearing.”

Follow-up questions

Police tensions heightened for the deaf community following the death of Sanchez, a 35-year-old deaf and nonverbal resident of Oklahoma City.On Sept. 19, Oklahoma City police, responding to a hit-and-run accident involving Sanchez’s father, encountered Sanchez in front of the home he shares with his father. Clutching a long pipe, which served as a walking stick to ward off loose dogs, Sanchez advanced toward police, who ordered the pipe dropped. The officers’ commands were lost on Sanchez, who was not only deaf but suffered from developmental delays. As neighbors frantically called to officers that Sanchez was deaf, an officer, the first at the scene, fired a Taser while the second responding officer fired multiple shots. Sanchez was pronounced dead at the scene.

In the days and weeks that have followed the shooting, disability rights and justice advocates, as well as the greater community, have anatomized the case. Even to disability-rights advocates aware of police brutality against deaf people, the circumstances raise questions.

“What hit us to the core was that neighbors called out to warn the officers that Magdiel was deaf,” Sites wrote. “And still, he got shot and killed.”

Are Oklahoma City officers properly trained for interactions with deaf people? It’s a question Oklahoma Association for the Deaf can’t answer. The Oklahoma City Police Department (OKCPD) requires four hours of training on how to interact with the deaf and hard-of-hearing community, among other training for encounters with different ethnic groups, races and disabilities. Oklahoma Association for the Deaf hasn’t reviewed or consulted on the curriculum.

The deaf community wants officers better trained and better educated on interactions with deaf people. Perhaps more importantly, they want officers ready to apply those lessons in the field.

“It is time for change to happen,” Sites wrote. “We’ve been silent for far too long. The hearing population doesn’t know what is best for us unless they’ve worked directly with us. We have to continually and diligently protect our rights.”

Last week, deaf advocates with Oklahoma Association for the Deaf sat down with OKCPD leaders to discuss training. The department is open to developing new training for interaction with the deaf and understanding cultural competencies.

“We have the responsibility of serving the entire public, regardless of why they are or what disability they have,” Chief Bill Citty said when asked about training during a press conference following the shooting. “If we find things we can do better, then I can promise you we will do better.”

More concerns

The city’s fifth officer-involved-shooting of 2017 is under investigation by the department’s homicide division, as required for all officer-involved shootings resulting in the loss of life. The case will be forwarded to the district attorney, who could file charges.Police will be piecing together the case in interviews with officers and witnesses alone. Neither officer had a body camera, which Black Lives Matter Oklahoma City activists are calling into question.

“Why were the body cameras either not on or not worn?” asked Rev. T. Sheri Dickerson, the organization’s executive director, in an interview with Oklahoma Gazette. “Our organization championed implementation. Here it was, once again, not even proper documentation was provided because there wasn’t any.”

Oklahoma City police leaders responded that cameras were still making their way into the department. Later this month, the department will equip its patrol officers with body-worn cameras, as 200 body-worn cameras are introduced as part of a federal grant.

The movement also questions officers’ use of force. One officer deployed a Taser on Sanchez, while the other simultaneously fired his gun. A year ago, Terence Crutcher, a black man, was approached by two police officers after his vehicle broke down on a Tulsa street. One of the officers fired a Taser at him, while another fired their gun, killing Crutcher.

“The confines of police brutality are going to have to end,” Dickerson said. “It is devastating to our communities, all communities of color. It is just happening over and over again. Real change is going to have to be implemented to stop it.”

Current OKC police training calls for an officer to draw their gun when another draws a Taser. In the event the Taser fails, one officer has a gun drawn.

The family of Sanchez is calling for an independent investigation of the shooting by Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Justice. Black Lives Matter Oklahoma City also supports an independent investigation.

Questions by the family and community groups must be answered, said Dickerson.

Moving forward

In the weeks and months ahead, Oklahoma Association of the Deaf will continue to call upon the city’s law enforcement leaders to implement new training as well as its own training for members of the community. The organization is determined to prevent another tragedy and believes training must occur between both communities, law enforcement and the deaf.“We need to educate ourselves,” Sites wrote, “to protect ourselves in positions where we may encounter police and find ways to de-escalate potentially dangerous situations and inform [police] that we are deaf and unable to follow orders.”

Print headline: Being heard: Disability rights and justice advocates want reform in police training and practices following an officer-involved shooting of a deaf man.