Miriam Friedman Morris grew up surrounded by her father’s artwork, but many pieces were missing and the work that was most important to him was the work he did not discuss.

Born in Austria in 1893, David Friedman moved to Berlin in 1911 to study art. He began publicly exhibiting his works in 1919, and his paintings and portraits were published in newspapers and journals. However, most of this work was confiscated or destroyed when he, his wife and their infant daughter escaped from Nazi Germany to Prague in 1938, and still more was lost in 1941 when the occupying German forces deported his family from Czechoslovakia to Poland’s Łódź Ghetto. The sketches he made of life there were also confiscated and destroyed, and when the ghetto was evacuated, he was separated from his wife and daughter (neither of whom would survive) and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. There — and in the Gleiwitz I labor camp and on a death march to Blechhammer — Friedman saw unspeakable horrors with his artist’s eyes that he began to depict after the Russian army liberated him in 1945. He continued his lifelong work after marrying fellow Holocaust survivor Hildegard Taussig and moving with their daughter Miriam to the United States.

“I always knew my father was special, but as I got older, I learned he lost all his artwork, had nothing to show me of his pre-war fame,” Morris said. “So all I knew about him, really, was that he was painting the Holocaust. … Of course, he painted not only the Holocaust; he painted everything that captured his imagination. He loved nature, he painted landscapes, he loved to paint still lifes. He painted portraits. My house was filled with paintings from the floor to the ceiling, down the hallway, down the stairs, everywhere. … Upstairs were landscapes and portraits and happy things and still lifes, but when you went downstairs, you were facing the Nazis, actually. You could just sit and stare at it, wondering, ‘How could this happen?’”

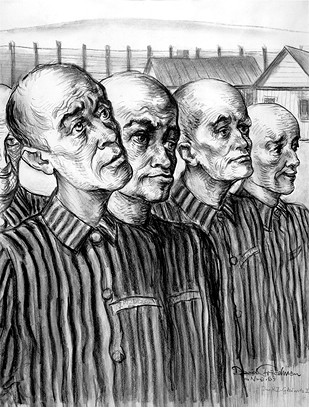

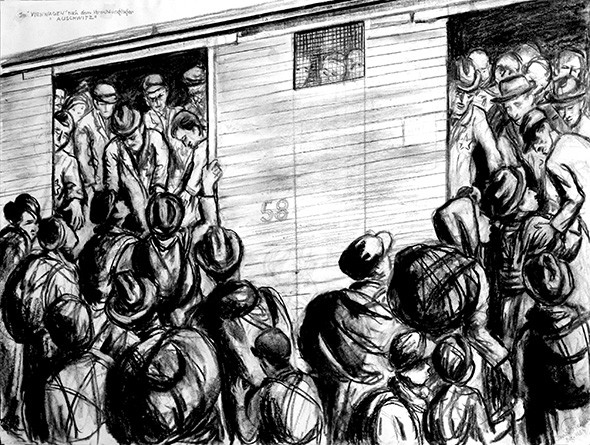

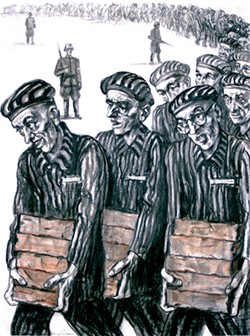

Testimony: The Life and Work of David Friedman is on exhibit through May 26 at Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, 555 Elm Ave., in Norman. The exhibition includes some of the artist’s portraits and landscapes along with Because They Were Jews, a visual diary of his Holocaust experiences featuring vivid illustrations with brief text descriptions.

Friedman’s caption for the charcoal drawing “Cattle Train to Auschwitz,” for example, reads, “This cattle train will go to Aushchwitz-Birkenau for the annihilation of all the people seen in this drawing. We were pushed and pressed like sardines and the conditions inside were terrible; we could hardly breathe. Three days without food too. I will never forget this trip. It was like a hell and this was only the beginning.”

The caption for “Roll Call in Camp Gleiwitz I” reads, “At six o’clock in the morning, everyone had to be in line and call his name. The block doctor would state the names of his sick prisoners. If anyone came late, they were beaten with an ox whip at least 25 times or had to walk on their knees for 50 yards in the snow. If anyone fell, they were also beaten. After roll call, the punished prisoners were transported to the barrack-hospital and were never seen again.”

Posthumous perspective

Though Morris remembers watching Friedman work on these and other drawings in his studio when she was a child, the scenes they depict were never a topic of conversation. After Friedman died in 1980, Morris discovered many of the unspoken details of his life by reading his diary.

“He didn’t talk about the Holocaust with me,” Morris said. “It’s not like we sat down and we were talking about that. He never talked about it, quite frankly. He didn’t need to talk about it because it’s all in his work. It was much too painful for him to talk to me about his first family. I learned most about my father from my mother, and then I learned more about my father after he died when I read his testimony, his own writing. It was very, very intriguing to me. I felt it very important to share what I could, and that’s what I’ve been doing. I’ve been sharing his mission to show his artwork to the world.”

Upstairs were landscapes and portraits and happy things and still lifes, but when you went downstairs, you were facing the Nazis, actually.Miriam Friedman Morris

tweet this

Using information from Friedman’s diary and with the help of art historians and collectors, Morris recovered many of her father’s pre-war artworks on several trips to Berlin, including hundreds of portraits he had drawn for German newspapers.

“He, in his lifetime, didn’t know about all the things that I found, and it’s kind of sad because I have so many questions that will remain unanswered,” Morris said. “My father is an example of a Jewish artist, not the only one, of course, who lost his profession because of the German Reich, and it nearly eradicated every trace of him. But because he was able to survive, he was able to paint again. … After the war, like many other survivors, he had to start from scratch. They had no identity. They had to prove who they were. They had to get new birth certificates. They had to worry about everything. They had nothing. They came out with nothing.”

Nothing but, in Friedman’s case, a mission to use his art to tell the world what he

witnessed.

In a diary entry dated Sept. 23, 1945, Friedman wrote, “I saw something new, something that never happened before in this century. I experienced this tragedy not only with my eyes but buried it into my inner being, into my memory to tear out at a more peaceful time. These were powerful images that I saw — to give form to all that misery — to show it to the world — this was always my intent.”

Morris will discuss her father’s life and art at A Night of Testimony 7-9 p.m. April 18 at the museum. Lorne Richstone, associate professor of music at the university, will lead an ensemble in a performance of five excerpts from works by Jewish composers whose careers were lost in the Holocaust.

“We have to remember my father survived so he was able to write his story,” Morris said. “We have to think about all those that didn’t survive and we don’t know their story. … Unfortunately, many stories will never be told, but I think everybody’s story is important.”

The exhibit and the presentation are free. Call 405-325-3272 or visit ou.edu/fjjma.