Erin Cooper offered a challenge: Name three famous female painters without saying Frida Kahlo or Georgia O’Keeffe.

Three might be too many, right?

“Seriously, think about that,” said Cooper, a 36-year-old artist, graphic designer, wife and mother of two living in Oklahoma City. “I think most people wouldn’t have trouble naming the top three male painters of all time, or the top five or the top 10 if they’re involved in the art world, maybe. But the list of successful female painters? That’s not a list anybody knows. And the subset of that list that I belong to is even smaller — how many successful woman, mother artists are there?”

She admitted that she can’t rattle off the names of dozens of female masters either (though it’s a sure bet she will top any national average), so she went to the public library and checked out a book, Great Women Masters of Art by Jordi Vigue.

“I just wanted to know who they were,” she said.

Mixed expectations

Cooper and her husband Tim, a prolific stone sculptor, each balance making art, raising their daughters and running CooperHouse, the graphic design firm they founded in 2011. This year, however, Erin decided to transition to a new schedule: She spends two days a week running CooperHouse and three days a week painting. Maybe it was one of the stunning financial realities with which new artists are often faced. Maybe it was a comment here, a snub there.

Maybe it was just one too many group art shows with all-male names on the promotional poster. However it began, Cooper said the more she waded into the art world’s murky waters, the more she began to notice differences.

“I’m not saying there aren’t opportunities for female artists, but I do think there are fewer,” Cooper said. “I honestly don’t think anything I’ve ever seen or experienced has been conscious on anybody’s part. This city is not only full of really good artists, it’s full of really good people. Most of the male artists I know here are really good, considerate people. It’s just little things that you start noticing after awhile.”

Cooper pointed to the recent explosion in the popularity of public art as an example of a system that’s slanted, intentionally or not. Depending on the size of the space to be covered and the amount of time an artist has to complete it, a public art project often requires round-the-clock work. That can present difficulties for a woman that some male artists probably wouldn’t consider before accepting a bid.

“OK, so I’d love to do more public art, right?” Cooper said when asked about some of the more recent large-scale, public work completed by male colleagues. “But I immediately think about childcare. That’s incredibly challenging, and it presents inherent difficulties when you consider that a mural is an immersive experience … I can’t just paint all day and hope my children feed themselves. It requires a great deal of planning and cooperation, if you even have someone to help you, which a lot of women don’t.”

For Cooper, painting all night on a project, something required more often than not thanks to either short windows of start-to-finish time or artists’ legendary procrastination skills, isn’t even an option.

“The obvious difference between a guy applying for that job and me applying for that job is that I won’t do that,” Cooper said emphatically. “I’m not going to stand alone under an overpass downtown all night with my back to the street without a bodyguard. Is that in your budget?”

When asked whether she’d ever been excluded more directly, she said yes but clarified that she thought it was not only largely unintentional, it was probably a reflection of the art scene and American culture as a whole. Cooper listed the names of several prominent male artists in the city.

“I don’t know all of those guys really well, but the ones I do know are good guys. The ones I barely know are still friendly to me at events, and I don’t think any of them would consciously do anything intentionally sexist, especially if they saw it that way,” Cooper said. “And I think it’s an easy thing to do, but when an opportunity comes along, it seems like it’s immediately pitched to one of their buddies. There does seem to be a core group of about eight or 10 of these prominent, male artists with influence in Oklahoma City, and they seem to always support and give opportunities to one another. And that’s great, but things like that can become exclusionary.”

Cooper said she sees similar discrepancies in the national scene, and they’re even more disheartening. A fan of painters Britt Bass Turner and Michelle Armas, Cooper broke down their work by price-per-square-inch and was stunned at what she discovered.

“Their price-per-square-inch is less than mine. How can that be? These are successful, well-known artists, and they still can’t charge more than I do? That’s terrifying,” Cooper said. “You know, recently, somebody decided that one of Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs was worth $58.4 million. There is no female equivalent of that.”

It bears mentioning here that Cooper is anything but (or maybe much more than) a squeaky wheel. An Oregon native, she enlisted and served for eight years in the Air Force’s visual information department. She moved halfway across the country to Oklahoma, a state where she knew exactly nobody, and dove into its art scene.

She still signs up for drawing classes and painting workshops, honing her craft relentlessly through private lessons with local legends like Bert Seabourn. Last year, she spearheaded the team that created the winning Taste of Western mural.

She and Tim have shown art together a few times, are both actively seeking solo exhibitions and are raising two curious and polite daughters while navigating the maelstrom that can sometimes pass for an artist’s life.

Complaining about nothing is not this woman’s style.

“When I see the playing field disparity, I feel like I’ve been smacked. I don’t need to be a rich and famous

painter, but I do want to be a successful one,” Cooper said. “And it’s hard because I need to feel like there’s something for me to aspire to.”

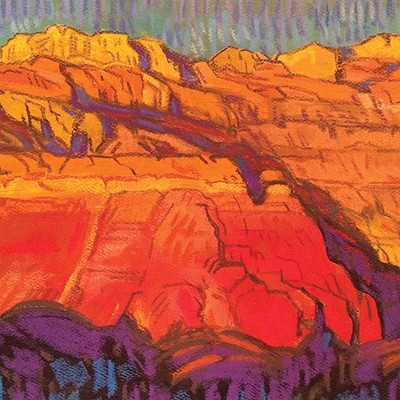

Cooper’s own work brings to mind her previously mentioned inspirations, Bass and Armas. Light, ethereal and feminine, her abstract expressionist paintings recently have begun to demonstrate something it seems Bass and Armus haven’t explored as much: contrast.

Cooper makes good use of stark, black lines that slice through soft fields of pastels and neon oranges with the eye of a much more seasoned painter. Furthermore, the progression of her portrait series (mostly of female friends and colleagues around OKC) makes it obvious that the drawing classes and sessions with Seabourn have paid off in a huge way, too.

Quality equality

So, is the Oklahoma City arts scene a bit of a boys’ club? If a hardworking, talented, focused painter like Cooper notices a difference in the number and quality of opportunities afforded to female visual artists, doesn’t the question at least bear examination?

In an effort to at least begin exploring the issue, Oklahoma Gazette asked the owners of five local art galleries, In the last calendar year, how many female or mostly female art shows have been displayed in your gallery?

Two of the galleries interviewed displayed one female artist between them since 2014, although the owner of the gallery where she showed said that exhibits are granted on a submission basis and she was the only female artist to ask.

However, two other galleries geared more toward group shows said they had more female art shows than they could remember. Of those two, one gallery owner said there have been multiple group shows that were all women, though the show’s premise wasn’t always gender-specific. The other owner offered math to back it up and said 54.5 percent of the gallery’s shows had a female artist as its “forward feature.”

The last gallery owner to be interviewed, Lisa Jean Allswede, has shown female artists exclusively in the Paseo Arts District’s The Project Box since it opened in May 2014. A working artist, Allswede uses The Project Box as her studio while overseeing what might be the most consistently rotating art gallery in town.

“After my daughter was born, I really needed to be around people who understood where I was coming from,” Allswede said. “I do think it’s harder for us because of how society has pegged us as a gender. We’re still supposed to be caregivers, and men are still supposed to be hunters and doers. But that’s changing.”

When asked what the end goal looks like, Allswede sounded eerily like Cooper.

“The same playing field; that’s all we’re after,” she said. “I don’t want to be included in a show because I’m a woman. I want to be included in a show because I’m a badass.”

Print Headline: Creating parity, Some say a noticeable sparsity of female artists reflects our community’s larger social proclivities.