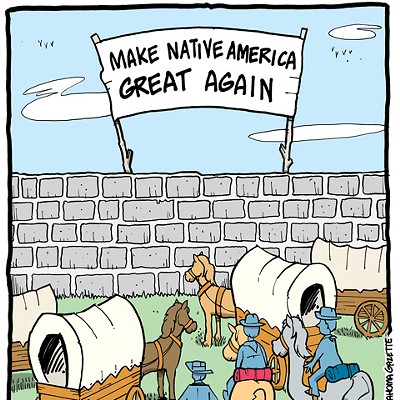

Oklahoma's lottery, approved 2-to-1 by voters in 2004, promised it would fix a funding gap in the state's K-12 educational system, conveniently deferring some of the difficult decisions legislators and state residents have not had the political will to confront.

So instead, we got a state lottery, which further promised to bring back to

Oklahoma all the gambling dollars " those not already being vacuumed up by our Native American casinos " that were going into the Texas lottery and other regional, state-sanctioned gambling ventures.

Oklahoma schools were promised an iron-clad 35 percent of lottery revenues, estimated by lottery backers at $150 million a year when sales began in 2005 but which have generated only about $300 million for education since inception. That's less than half the expected take, despite the myriad ways the lottery allows one to be separated from one's folding money.

News flash: Fewer people are playing Oklahoma lottery games not only because Arkansas succumbed to the same inane state revenue-enhancing, school-fix-it idea, but because our state finally has been engulfed by the worst, longest-duration, national economic recession since the big one back in the '30s. Everyone's revenues are down, from the corner coffee shop to the four major tax categories tracked by the state treasurer, which, collectively, were more than 25 percent below plan in the December fiscal-year half-time report.

Now we are told the Oklahoma lottery should abandon the 35 percent school split, which was a key selling point for voters, as many other state-sponsored lotteries eventually also conceded was necessary. The lottery has found a champion in state Sen. Richard Lerblance, D-Hartshorne, who will introduce legislation this session to remove the fixed allocation on the basis that lottery prize money could be increased and more payouts could be offered, which theoretically would attract more players.

Let's face it. State-sponsored lotteries are not-so-hidden, regressive taxes on the get-something-for-nothing crowd, many of which may be the least able to afford gambling losses.

A "flexible" school allocation formula, code for further depriving our children of funding for what's already deemed a comparatively abysmal K-12 education in Oklahoma, would let unelected state lottery officials decide how much money actually goes to education and how much more money would go into advertising and promotion to attract even more math-challenged dreamers whose likelihood of winning is nearly nil.

Well, what else would you call a scheme " Powerball, for example " in which your odds of winning a gazillion dollar grand prize (about one in 150 million) are far smaller than your odds of being involved in a serious automobile accident on the way to buy the ticket necessary to play?

Here's a thought: If Oklahoma school funding needs attention, then fix school funding properly, based on taxes approved at the ballot box, but disconnect the already fraying tether to the Oklahoma lottery.

That's why many opposed establishing state-sponsored gambling in Oklahoma in the first place, because it premised on paying guilt-assuaging indulgences to the school system in order to get the lottery created.

Let the Oklahoma lottery, which by all means should be given access to the wallets of consenting adults, stand or fall on its own merit as a source of state revenues. And if, at some point, the lottery's prize payouts and overhead begin to consume all its revenues, it can be put out of its misery without a fuss about "the children."

Hazelton is an economic adviser to the Oklahoma Bankers Association and an adjunct professor of finance at Oklahoma City University's Meinders School of Business.