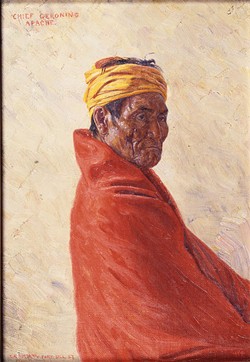

Before statehood, Oklahoma and Indian Territories captured the imaginations of an American populace that mostly would never get a chance to see the area firsthand.

The result, said Mark White, Wylodean and Bill Saxon director at the University of Oklahoma’s Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, is a wealth of art, paintings and imagery from the state’s pre-history.

“Indian Territory was a place most Americans had not visited and would not ever visit,” White said, “so imagery, just as much as the written word, would give them a sense of the really complicated situation that existed here.”

Picturing Indian Territory, 1819-1907 opened earlier this month and continues through Dec. 30 at the museum, 555 Elm Ave., in Norman.

White credited the idea for the exhibit to Byron Price, the director of the university’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West.

Around Oklahoma’s 2007 centennial celebration, Price began compiling a database of historic images from the Oklahoma and Indian territories.

He eventually suggested the museum organize a collection of images for a future exhibit.

“That was somewhat of a daunting process because he had compiled, at that point, well over 700 images of people, places and events,” White said.

Almost a decade later, the finished product is an exhibit featuring about 75 pieces collected from various sources, including Smithsonian Institution, other museums and different groups from within the state.

White said it was important to first understand what the key events in pre-statehood were before finalizing the exhibit.

“We wanted to do something which, to that point, had not been done, which is to look at the history through visual imagery,” he said.

Outside intrigue

Interest in Indian Territory grew nationally following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 that required several Native American tribes to move from their homelands elsewhere in the country to what was one of the nation’s most remote regions.Despite the forced removal of Native peoples to make room for the expanding population of the United States, many Americans were intrigued by Native life and customs.

“There was interest, as there had been decades before, in the perceived exoticism of the Native tribes,” White said.

Famous painter George Catlin, whose work is featured in the exhibit, was the first white painter to depict the Plains Indians in their native territory.

At the time, it was nearly impossible for artists or anyone to visit Indian Territory on a whim.

Artists who did visit the state often had to do so on a military or research expedition.

Picturing Indian Territory puts an emphasis on art that was created by those who experienced the area firsthand, although White said that does not mean their work was without bias.

“Sometimes even what they saw here they tended to exaggerate or distort for their own purposes,” he said.

Interest in Native culture eventually broadened into a love of the romanticized American West.

“By the end of the 19th century,” White said, “there is this continuing interest in the native tribes, but there’s also this interest in Western culture that was popularized by Wild West shows like that of Pawnee Bill.”

The last years of the territories and the early years of statehood are marked by general excitement surrounding the Oklahoma land runs.

Contrary to popular belief, Oklahoma had not just one land run, but several between the years of 1889 and 1901.

White said the land runs were often depicted in the popular press, including publications like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, both the equivalent of what a publication like Time magazine has been in the last few decades, focusing on textual and visual coverage of news and events.

The state’s land runs were the first time any land had been claimed by virtually whoever was the fastest.

White said the events were so exciting and unique that they made often made international news.

Continuing relevance

While other places have become diasporas, White said few, if any, can claim such a diverse combination of people as the many tribes forced into Indian Territory.The result is a complex history of political dynamics in the region.

“What the exhibit ultimately proves is that Oklahoma, in its former incarnations as the Indian and Oklahoma territories, has a very complicated and unique history,” the director said. “There are things that have happened here that really set it apart from any other state in the country and, I would say, also the world.”

Oklahoma history is far from the museum’s sole focus, but White said it does have a special interest in showing how things that happen here impact the nation and world.

“We like to be able to demonstrate that what has happened here and what continues to happen here does have a relevance outside of the state’s borders and that Oklahoma, in many ways, is a very interesting state,” he said.

Visit ou.edu/fjjma for more information about the museum and exhibit.

Print headline: History looks, Picturing Indian Territory, 1819-1907 paints a picture of Oklahoma long ago.