Between 140 and 160 law enforcement officers are killed in the line of duty in the United States every year, according to the group Concerns of Police Survivors (or C.O.P.S.).

C.O.P.S. is a national nonprofit that provides resources for the surviving family and affected co-workers of a fallen police officer.

My daughter, Stephanie, a licensed professional counselor in Edmond, works at the C.O.P.S Kids Summer Camp each July in Wisconsin. The camp "provides surviving spouses with children (ages 6-14) the opportunity to work with professional counselors and trained mentors to improve communications within the family unit and resolve grief issues together," according to the C.O.P.S. website.

The guiding belief is that if the surviving parent doesn't heal, the child won't either.

The ramifications of such a tragic and public death make coping hard for the surviving spouse and children. One hot day on the way to get ice cream recently, Stephanie mentioned the difficulty grieving families have in dealing with the media.

I see a lot of advice for journalists on how to deal with grieving survivors, but I see very little advice for grieving survivors on how to deal with the media.

No doubt, the media are the last thing on surviving spouses' minds when tragedy strikes, and they may be taken aback when a reporter approaches or calls. They may not be thinking clearly, perhaps not realizing that the family has no obligation to talk to the media.

"I remember after the Murrah building bombing, some families want to talk," said Charlotte Lankard, an Oklahoma City marriage and family therapist. "You've got some people (who) really want to talk. I think for those people, it probably serves a good purpose because part of working through grief is telling your story and having it validated.

"Other people get very private and don't want any attention drawn to themselves," she said.

Those unaccustomed to dealing with the media are vulnerable, with children most at risk. It's a good idea to get privacy and confidentiality ground rules clear before an interview begins or before going on camera.

Lankard said reporters quoting children could bring ridicule or teasing from peers.

"It can put some sort of label on them," she said. "It can cause people to judge them or to go overboard in telling them how wonderful they were to do this. I just think we have to be really sensitive to all ages, but particularly to children and teens."

Many reporters " rookies and veterans alike " have difficulty interviewing grieving family members, although they're trained to empathize, listen and treat survivors with dignity and respect.

Reporters "have a responsibility to report the truth with compassion and sensitivity," according to the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma, a project of Columbia University's School of Journalism.

Joe Hight, past president of the Dart Center's executive committee and director of information and development at The Oklahoman, said people are in shock after a tragedy, a most difficult time in their lives. It's not something they want to deal with.

"What's most important is to decide what they want to get out, the story about who this person was and why the death would have a ripple effect on so many people. For the most part, the media wants to tell that story."

He said he realized it seems like intrusion, but it's a story that could be remembered for years. He suggested the family consider selecting a representative, someone who's good with the media and wouldn't mind doing it. The family should also make funeral directors aware of the information they want made public.

"I see journalists as people who are writing our history," Lankard said, "so I'm certainly not opposed to interviews. But what we have to do is be careful not to shame, not to embarrass, and make sure that what we say is accurate and in the context of what happened."

Lankard, who writes a weekly newspaper column, said she would tell grieving survivors to be honest with reporters and to ask questions.

"I would say, 'If you want to print my name and my story, I have to see it first.' A lot of reporters would not do that, so OK, you don't get the story. I think they have to speak up," she said.

Reporters may hedge at allowing prior review of the story " and deadlines may prevent that in news situations " but most will double-check accuracy and read quotes back to a source. They identify themselves and ask permission to talk with a survivor, making clear what information they're seeking and when publication is expected. They also give survivors the opportunity to add any information they wish at the end of the interview.

Stephanie is checking flights to Wisconsin and preparing for another summer with "her kids." The C.O.P.S. Kids camp helps survivors after the fact. Wouldn't it be wonderful if there were a camp that prepared us for the unthinkable?

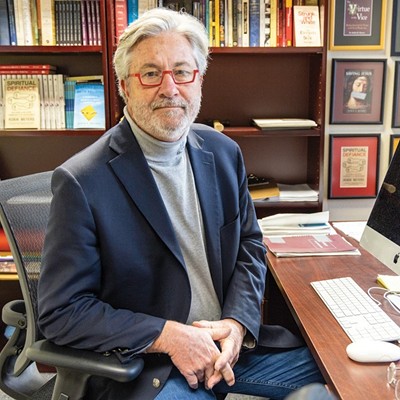

Willis, a former Muskogee Phoenix managing editor, teaches public affairs reporting at Oklahoma State University.